France Day 3: Late to Bed, Early to Rise

Whoohoo! Four whole hours of sleep. I'm up, so I might as well write. Here's some more food for thought:

There are over 300 producers in the Armagnac region, and by producers I mean people who grow Armagnac grapes (baco, folle blanche, colombard, ugni blanc). Because there are few actual distilleries, being a producer means you have a farm, you harvest grapes, you make wine, and that wine gets distilled - either by you or someone you hire to do it. The result goes into barrel and sits in your barn or warehouse until it gets sold to someone like Darroze, or bottled for Armagnac customers. Because one doesn't need to own a still to be a producer, the number of possible producers is suddenly limited only to the number of farmers growing the necessary grapes. There are a lot of people growing grapes and making wine in Southwest France, therefore there's a ton of Armagnac out there. That's a compelling fact and a very exciting idea if you're looking for the new frontier in spirits.

The last day has completely changed everything I thought I understood about distilling. You always hear that pot stills provide the real flavor because the base liquid being distilled isn't constantly re-introduced back into the mix. When distilling on a pot still you have to boil the booze and capture the alcohol, keeping the cut of distillate you want and either dumping the rest back in later or using it for disinfectant. Pot stills are always considered a more pure method because they're not as easily automated. According to Armagnac producers, however, with brandy, a pot still isn't really the best option for pure flavor. Of course, they could be just saying that, but let me explain their reasoning.

The left side of the still pictured above in the second photo is where the wine is boiled and vaporized, while the right side is where it is condensed back into a liquid. Unlike a standard pot still, which has nothing but an open chamber between the liquid and the neck at the top, the alambic Armagnac still has a series of plates, as you can see have been removed in the picture above, through which two mutually beneficial actions occur - one going up and the other going down. As the vapor rises, the plates help to filter out the heavier alcohols and force them back down into the wine, allowing only the desired ones to pass through. At the same time, the wine being distilled is pumped in from from above so that it travels down into the boiling pot via these plates. That means the vapors going up must pass through the wine going down. As the vapor intermixes with the wine, it grabs more of the inherent flavor before finally making it's way to the top.

If distilling wine in Armagnac is ultimately about grabbing the inherent flavor of the wine, then as a farmer you've got four choices as far as varietals. Baco used to be the grape of choice, but we quickly learned this was only because baco was resistant to phylloxera. The grape itself doesn't have a load of personality, which makes it a pour choice for normal table wine, as well as a blank canvas for new oak. However, it does produce brandies that can age very well in the 30+ year old range. Therefore, if you're interested in creating rich, supple, and extra mature Armagnac, then baco isn't a bad choice. However, you won't be able to sell any baco wine to supplement your Armagnac income and the younger brandies will be less interesting. Most producers who are serious have switched over to the other three grapes, with folle blanche being the crown jewel. Because of its tempermental ways, folle blanche is difficult to grow and tough to mature, but because distilling wines need high acidity, the farmers can pick earlier than vintners looking to bottle something drinkable.

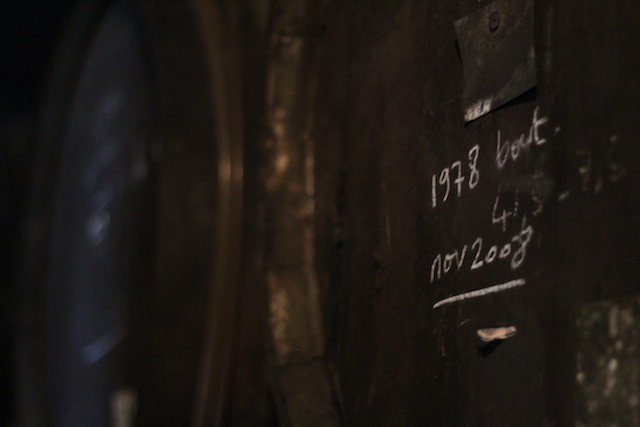

Then you've got the whole cooperage aspect to think about! New oak? First fill? If so, then for how long before you transfer it to an older barrel so the the wood maturation slows down? Mr. Darroze told us that new oak sets the foundation for an Armagnac and, "like a house," a brandy needs a solid foundation before anything else can be done. When we were walking through the warehouses of Scotland, we saw things like 1993 Bladnoch or 2000 Bruichladdich written on the side of the cask, however, single malts are so much easier to understand!! You can tell what type of barrel the whisky has been aged in by looking at, how old it is from the date, and who made it from the name. When we see an Armagnac barrel that says 1978 only know the age and where it's from based on who we're visiting. What varietals were used to make it, however? Baco? Folle blanche? A blend of both or perhaps ugni blanc as well? How long did it spend in new oak? What fill was the barrel it was then transfered too? What was the vintage like that year? For that particular varietal? Maybe good for baco, but bad for folle blanche. How long should it be aged based upon the quality of the vintage? All of these aspects affect the flavor and for that reason there are many different flavors of Armagnac.

We tasted Armagnacs yesterday that bourbon lovers would die for. Rich, woody, spicy and powerful. Lot's of barrel character. Some are bold at a cask strength high proof, some are more mellow, but few are dilluted with alcohol. If the brandy is at 45% it's because it naturally evaporated to that point over time. Almost everything we tasted was completely uncut, from a single barrel, and totally drinkable without water. These are important factors for spirits geeks like us. Even though Armagnac has been produced for over 700 years, no one here is blindly stuck in tradtion. The producers are adapting and they're giving passionate drinkers what they want. There is so much variety and potential here. Plus, unlike whisky makers, the producers have to do the viticultural side as well. We're celebrating master distillers in Whiskyland, meanwhile the Armagnac producers laugh at that idea. For them, distilled spirits begin in the field. It's a lot to take in, but I think Armagnac is going to be a big player for K&L in 2012.

Wait until you taste some of the bottles we plan to bring in. You'll see what I mean.

-David Driscoll