Scotland - Day 4: Glenfarclas

Just outside the town of Aberlour, not too far from the mighty river Spey, sits Glenfarclas distillery - one of the last family-owned, independent single malts in Scotland. The Grants have owned the site since they purchased it in 1865 for 511 pounds and we were driving in to meet with George, son of John, who currently runs the operation. He had agreed in advance to let us run rampant through the warehouses, open every barrel in sight, and take what we liked. With more than 55,000 casks on hand, we knew it was going to be a tough job, but somebody had to do it.

Although technically a part of the Speyside region, Glenfarclas is known to me as a Highland malt (although they do put Speyside on their label in small font). Up until about forty years ago, the region was actually known as Glenlivet, and Glenfarclas was recognized as a part of this appellation. The confusion between the regional name and the distillery Glenlivet was eventually deemed too confusing, however, so the the Speyside region was created to ease the possbile misunderstanding. As long as a distillery is withing a certain distance of the river Spey, they can use the name Speyside. Some distilleries, like Macallan, choose not to and claim the Highland label instead. After passing Aberlour distillery, we turned off from the river Spey and took the road towards the facility. Driving up the path to the buildings the hill of Benrinnes stands starkly in the background, brooding and solumn against the dark grey sky.

Hanging in the distillery upon entrance is a painting from 1791 that shows the distillery and the farm that once accompanied it. Although Glenfarclas was legally founded in 1836, the Grant family is unsure as to when it was actually built or who even built it! According to the artwork, the distillery exisited at least forty or so years before its foundation, likely because the original owners did not want to pay the tax that came with whisky production. It's therefore quite possible that Glenfarclas could be much older than we know.

Although Glenfarclas is one of the smaller distilleries in Scotland, they still pump out way more juice than Laphroaig, Lagavulin, or Highland Park. With about 3.5 million liters of production a year, the distillery uses about two truck-fulls of barley every ten hours - over sixteen tons. Their mash tun is huge, mixing up grist with hot water and yeast in gigantic amounts.

Glenfarclas uses metal washbacks instead of wood because they believe it causes fewer problems with the fermentation. Like any proper scientist, the Grants have experimented with wooden vats, but found that bacteria could be hiding in the wood and sterility was generally more difficult to maintain. They're able to get about 10% abv on their wort, which is quite high compared to other distilleries. George praises the conductive ability of the tanks to maintain heat, helping the yeast eat more of the available sugar.

Apparently, stones often get caught in with the barley, which constitutes the need for a de-stoner (cough, cough). We had fun with that name.

The stills at Glenfarclas are heated by direct flame underneath, a rarity these days for a distillery. The flame causes the barley to stick to the bottom, like rice in a hot pot, so rummagers are needed to keep stiring the grain. Much like their experiment with the washbacks, Glenfarcas at one point did try a steam-heated coil to power one of their spirit stills, but the whisky tasted flat and without the usual sweetness. They immediately tore it out and put the flamethrower back in.

This is the only way to taste whisky! In a proper Scottish lounge, complete with leather chairs and mahogony tables, with the Grant family tartan adorning the carpeted floors.

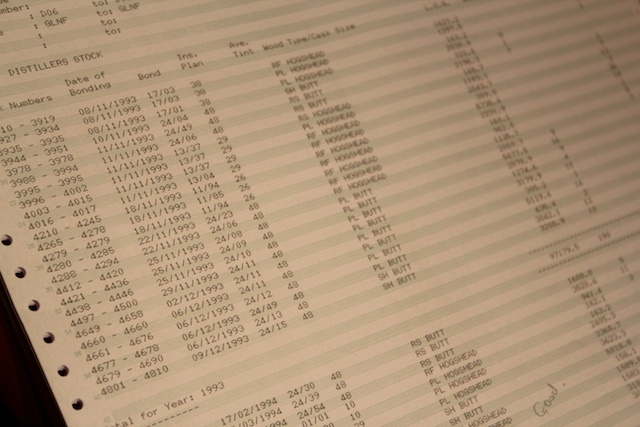

George busted out his massive list of casks, printed on paper fresh from the late 80's.

We tasted some of the Family Cask releases to get an idea of what we liked in the meantime. Vintages with whisky are not at all like wine, where the crops vary in quality depending on the weather. Other happenings affect a vintage for whisky, such as who coopered the barrels that year. It wasn't until 1990 that Glenfarclas began using the same wood on an annual basis, so the cask quality can be better in certain years. Oil shortages in the 1970's slowed production and cork shortages in the 1960's affected casks, both affecting how the whiskies were produced. The vintages at Glenfarclas are all very different, yet casks from a certain vintage are remarkably consistent with one another.

One vintage that was very consistent and incredibly delicious was 1979 - the year of my birth. All of the casks from this year were fourth-fill sherry, so the influence of the sweet wine is mild at best. The complexity of this whisky absolutely blew my mind. David and I grinned at each other while George searched out the location of other 1979 barrels in the many warehouses.

Deep inside the dark, dank barrel houses we tasted. And tasted. And tasted. For hours we popped corks, dipped into some bungholes, and sampled whiskies from 1965 up to 2000. It took incredibly stamina and endurance to keep going (I'm being entirely serious!).

And what did we come away with? We came away knowing that Glenfarclas is one f-ing awesome distillery and that George Grant is a top-notch guy. Some of our favorites, besides the 1979, were quite old and quite expensive, which left us torn. While we continued to search through the younger casks in search of a hot deal, those whiskies just weren't ready yet. They still need time, or they will need to be blended. There was no amazing twelve year old cask that could blow the standard Glenfarclas 12 out of the water because, at that age, it can't stand on its own yet. We figured out that, for the price, there was little reason to fool with the younger vintages. The blenders are already doing an outstanding job with the current selections we have at K&L, so it would be best to just supplement those with exciting, higher-end options.

In the car ride over to Pitlochry, where I'm now lying on my hotel bed typing this, we knew our strategy had to change a bit. Last year we came looking for deals because we didn't know how much we could sell. This year we know we can sell it, so we shouldn't just worry about the price - we simply need to choose the best casks available and get them to K&L. At Glenfarclas, the best whiskies were expensive, but trust me - they were absolutely unreal. Best of all, there's nothing that tastes like them on the U.S. market. Whatever we choose to purchase will be exceptional and will be sought after worldwide once the word gets out.

Off for a bite to eat!

-David Driscoll