Scotland - Day 10: A Bit of History

The history of whisky distillation in Scotland is long, complicated, and in some circumstances difficult to trace. Hundreds, if not more, of distillers since the beginning of single malt distillation have chosen to remain illicit, favoring the risk of penalty over the taxation they would face were they to register with the government. Choosing to become a licensed distillery meant serious business. Because one was taxed on every liter distilled, one had to make sure there was a market awaiting what eventually was produced. This meant that staying in business was quite difficult, especially for isolated distilleries that were tough to reach with commercial transportation. In the 1800's, the government passed a series of laws that made it easier for smaller distilleries to deal with the burden of taxation, hoping to persuade them into the system. I've spent the last few days pouring through some history books, which detail the battle between the industrial distillers of the Lowlands, churning out grain and malt in massive amounts, and the smaller, illicit distillers of the Highlands, who were making better whiskies on smaller stills, winning the favor of true enthusiasts everywhere, despite the fact their product was technically illegal. Another book documents the collapse of Campbeltown, after the disastrous speculation by one Mr. Pattison that brought down his own giant operation along with the distilleries of many others who had invested with him.

For all that whisky history on the Scottish mainland, I had found little concerning the islands, particularly Islay, where we have been staying for the past few days. Granted, I haven't been scouring the internet in search of it, just looking through the available whisky texts. It wasn't until we visited Kilchoman, a farm distillery much like the ones no longer in existence, that we found some fantastic information. Part of their visitor's center contains a map of the island, a list of the island's fallen distilleries, and a vague direction as to where we might find what remains. Because the information is printed onto a giant board on the wall, I was forced to take several photos of the map and the list of distilleries, load them onto my computer, and then zoom in on the text as needed. I thought it would be interesting just to pass this history on to you readers. However, after finishing early at Caol Ila and having an entire afternoon in front of us, David and I decided to use our free time to track down the actual sites and document what was left. We went at it without any real map, directions, or sense of what we were looking for. Asking people we met along the way proved to be the best and fastest method. This isn't meant to be a deep, fully-researched attempt to uncover anything new, just a fun and hopefully entertaining attempt to provide some travelogue and photography to some interesting information.

All of the historical information I have re-typed here on the blog comes from Kilchoman Distillery who credit Graham Fraser for allowing them to publish it. I have taken much of his text directly from the distillery, except for a few instances where I paraphrase him for the sake of editing. All of his information is presented in italics as to separate his own work from mine. His historical research allowed us to have quite an afternoon, so we thank him for providing true whisky fanatics with the chance to learn more about Islay. It's no secret that I'm a sucker for Scotland's lost distilleries. It's always more exciting to taste something that will never again be produced, but it's always tastier with a little bit of background information.

Leaving Caol Ila, we headed back towards Bridgend down the A846. According to the map, somewhere east of Ballygrant laid the remnants of Lossit distillery, located upon the farm that still remained. We only saw one road heading east when we entered Ballygrant, so we took it and kept our eyes peeled. We eventually decided we had gone too far, so we turned back around to retrace our steps. Upon our return, we flagged down a local farmer who told us that we had indeed passed the turnoff to Lossit farm. We needed to make a right up ahead and head another three miles down a narrow, country road. When we arrived, however, there was a clear sign at the entrance which read "Private Road. No unauthorized vehicles past this point." Debating whether we should proceed or not, we eventually decided not to out of cowardice.

Lossit Distillery - est. 1826 - Lossit Distillery was located at Lossit Kennels, not far from Ballygrant on the minor road to Lossit Farm, close to Loch Ballygrant. It was a medium-sized farm-scale operation and in 1826-7 it produced 12,200 gallons of proof spirit. It was in operation under various men until 1862, making it one of the longest surviving 19th century farm-scale distilleries on Islay. There is a possibility that Bulloch, Lae & Co used the Lossit warehouses (perhaps to store Caol Ila whisky) until 1867. Today the house and kennels remain, although where whisky distilling actually took place remains a mystery and there is nothing left of the warehouses.

Further down the A846 were the lost sites of Daill and Scarabus. We couldn't find the turnoff to Daill and the exact site of Scarabus is still unknown, so we decided to pass on these two, but the information about them is below.

Daill Distillery - est. 1814 - Daill Distillery probably operated as a farm distillery after the Small Stills Act encouraged distilleries to go legitimate. The distilling operation was, throughout its short life, in the hands of the McEachern family from 1815-34. By 1827, it had an annual output of 6,043 gallons of proof spirit. It's demise, like that of many inland distilleries on Islay, was probably sealed by the difficulties of transporting the product to the mainland markets. Buildings in remarkably good condition at the Daill farm exist, and these could well have been the location of the McEachern family distilling operation.

Scarabus Distillery - est. 1817 - One of the most obscure and short-lived farm distilleries on Islay. A license was taken out in the name of John Darroch & Co for the year 1817-18. It seems likely that this was an opportunist attempt at distilling following the 1816 Small Stills Act as records reveal a 76-gallon, single still operation in 1817-18. Scarabus Farm exists, although whether this was the exact location of the distillery and what happened to it after its two short years remains to be discovered.

When we arrived in Bridgend, we parked the car and took a quick look around the small town. There were once two distilleries nearby, but their exact locations are unclear.

Bridgend Distillery & Killarow Distillery - est. unknown - Details of these two (or three) distilleries located at the former island capital, Bridgend, are very limited. David Simson is on record as operating a licensed distillery at Killarow until 1766 when he moved to Bowmore to establish the distillery that survives today. It's exact location is unknown. A Bridgend distillery was custom-built by Donald McEachern in 1818 with a wash still of 146 gallons producing single-distillation whisky. It was then run by his son Donald between 1818-21, when the company was wound up and ceased operations. Information exists that suggests a distillery was licensed to a J Macfarlane at Bridgend around 1821, with an annual output of 3,937 gallons (perhaps a new owner for McEachern's distillery?).

Could Bridgend distillery have been located next to where the Bridgend Hotel now stands? I should probably do some more research before positing such a question, but I'm on a buy trip right now and am trying to get this done in one day during my free time! What do you expect?

Rather than continue down the main A846 into Bowmore, we took the narrow turnoff onto B8106 and headed due south towards Port Ellen. Somewhere off of this road were the former sites of two smaller farm distilleries – Mulindry and Tallant. According to Fraser, nothing remains at Mulindry, which would make finding its location a bit tough for two amateur hunters like ourselves, especially with the vaguest of vague maps and only about fifteen minutes allocated to find it. We didn't see anything that would lead us to the site, so we decided to keep our watch westward in search of the Tallant farm.

Mulindry Distillery - est. 1826 - This is perhaps one of the shortest lived and unlikely distilleries on Islay. Built by John Sinclair in 1826, it operated at a site beside the junction of the Neriby Burn and the River Laggan, next to McNeill Weir (the start of the Bowmore Distillery lade) and its machinery was water – powered from the nearby river. Its output in 1826-7 was 4,332 gallons of malt whisky. Sinclair, according to the local Excise officer in 1831, liked his own production a little too much, which may account for his bankruptcy that year and emigration to America. The distillery appears never to have reopened and today all that is left is a pile of overgrown stones and derelict croft.

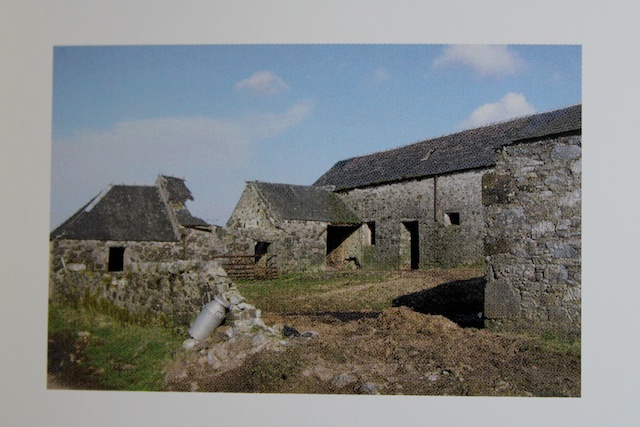

There was only one turn off and one farm anywhere near the area where Tallant was supposed to be and that road was blocked by a fence halfway up. I hopped out and snapped a photo of what should be Tallant farm and the site of the lost distillery. David also found the picture below in a history book, so I snapped it with the camera.

Tallant Distillery - est. 1821 - This distillery was established in 1821 by the brothers Johnston at Tallant Farm, near Bowmore. Excise records until 1827 show this distillery recorded as one of two 'Bowmore' distilleries. It appears to have been a true farm-scale operation with Angus johnston listed at one point as distillery manager. It was never, however, a profitable commercial operation, perhaps in part due to the generous drams John provided to visiting workmen and farmers. Output was as low as 220 gallons and reached 2,101 gallons in the year 1826-27. The business folded in 1852, although the Johnston family would go on to become successful distillers at Laphroaig. Tallant Farm exists today and many buildings from those distilling remain, albeit some in a state of collapse.

We had to go back to Laphroaig anyway because David had forgotten his notebook there, so that gave us a chance to locate the remnants of Ardenisteil, located adjacent to the current Laphroaig site. According to Fraser, part of what remained was still currently in use by Laphroaig, so we would have a chance to photograph a few buildings. The woman in the visitor center told us to go back up to the car part and head down a dirt road just a bit further south from the main distillery. The few buildings left from Ardenistiel would be at the end of the path. We walked along the dirt track, filled in with lush patches of green grass, and fenced in by old stone walls. According to the history book provided to us by Laphroaig, the distillery itself was demolished and warehouses were built on its site. What remained would likely just be surplus housing. The receptionist told us that these buildings had been turned into a modern house, looking very little like a dilapidated distillery.

Indeed she was right. A beautiful estate awaited us with views of the water all the way down to Ardbeg.

Next to the house are a few old storage buildings and a shed, which were likely used by Ardenistiel.

Ardenistiel Distillery - est. 1836 - After the successful establishment of Laphroaig in 1816, a farm tack was leased by the financiers for the Ardenistiel Distillery, who then put it in the capable hands of two young distillers. They ran it until 1847, operating on a site immediately adjacent to Laphroaig. Ardenistiel was then assigned to John Morrison, a previously unsuccessful manager at Port Ellen. He was unable to make a go of it and only remained until he was sequestered in 1852. The management changed hands a few more times and eventually Ardenisteil was only running at half capacity to save money. By 1866, it went bankrupt and by 1868 the facility was already dilapidated. The buildings were eventually taken over by Laphroaig and are a part of its offices and warehouses today.

Since we were at Laphroaig, Lagavulin – the site of two lost distilleries – was just a quick drive away. We were instructed by the receptionist as to the location of the former Malt Mill, which was located in a small office behind the main entry way. It appears that everyone envied and wanted to be like Laphroaig back in the day. Read on...

Malt Mill Distillery - est. 1908 - When Sir Peter Mackie lost his bitter legal dispute to retain the sales agency for Laphroaig whisky in 1907, he reacted in charismatic style by deciding to make his own 'Laphroaig' type whisky and in 1908 build a traditional small pot-still distillery within the Lagavulin complex. Despite hiring staff from Laphroaig and attempting to copy the Laphroaig recipe, it did not succeed, perhaps because it used a different water source. Malt Mill tried to replicate a traditional style of Islay whisky using only peat dried malt, and it is reputed to have had heather added to the mash. It was always a small-scale operation producing 25,000 gallons of proof spirit in its first year, compared with 128,000 gallons at Lagavulin. What is perhaps surprising is that it survived until 1962 when it was merged with Lagavulin and its coal-fired stills moved to the latter's still house for another seven years use. The Malt Mill distillery building is now the reception center within the Lagavulin site.

Neither Georgie nor the receptionist were clear as to which buildings once housed Ardmore distillery, but Fraser claims that the still house, tun room, and malt barn no. 4 were listed as part of Ardmore, so that's what you see above.

Ardmore Distillery/Lagavulin 2 - est. 1817 - Little is known about the Ardmore Distillery which shared the sheltered bay at Lagavulin with Lagavulin distillery. It was established in 1817 by Archibald Campbell, although when the name Ardmore was adopted is uncertain. It opened as a 92-gallon, single wash distillery, but within a year was operating under double distillation with the addition of a 30-gallon low wines still. By 1825, it was being operated by John Johnston of Lagavulin who ran both distilleries using the names Lagavulin 1 and Lagavulin 2 (much like Clynelish and Brora formerly existed as Clynelish 1 and 2). Johnson died in 1836 and in 1837 a valuation was run. The still house, tun room, and malt barn no. 4 were all listed as belonging the laird Walter Frederick Campbell, as Ardmore Distillery. However, Johnson was in debt to a Glasgow distiller-merchant named Alexander Graham who ended up acquiring Ardmore and merged it with what is the present-day Lagavulin site.

The way back to Bowmore leads through Port Ellen, so we pulled over and had another look. We had snuck into the maltings site last year (completely off limits to us and anyone else not working for Diageo). You can't really get a good shot of the Port Ellen painted against the warehouse anymore because the ferry, which no longer lands at Port Ellen, offers the best chance for that shot. All boats land at Port Askaig now, so at some point I'll have to dig up last year's photo from when we landed here.

There's nothing really left from the actual distillery at Port Ellen even though the buildings are still in tact. It's now 100% dedicated to malting for the just about every distillery on the island. The warehouses are still there located along the water.

The pagodas are still there as well, but you have to sneak in the back entrance way to get a good shot.

Port Ellen Distillery - est. 1825 - Established in 1825 by the McKay family, it was operated by John Morrison & Co from 1831-34. John Ramsay and later his wife ran the distillery from 1836 until 1920, during which time they expanded the distillery. It was eventually acquired by DCL who mothballed it from 1929-67. Production buildings were then re-built by DCL and the distillery operated from 1967-83 when it was closed again during the whisky rationalization of the 1980's. As DCL already had two other Islay distilleries, Port Ellen was tragically thought to be surplus to requirements. The original distillery buildings remain today, linked to the Port Ellen Maltings complex.

I'm realizing now that we completely forgot to search for the Newton distillery, so I'll include it now. No photos, however. Sorry!

Newton Distillery - est. 1819 - The Small Stills Act of 1816 encouraged quite a few individuals to take out distilling licenses and in 1819 Thomas Pattison opened a farm distillery at Newton, located off the Bridgend to Ballygrant road. Newton produced 6,122 gallons of spirit in 1826-7. It operated continuously until 1837, by which time most farm-scale distilling operations had closed on Islay. Little is known about the operation of the distillery although there is still and outbuilding at Newton House that could have been part of the distillery and the metal bars on the windows are perhaps signs of previous use as a bond.

The last two sites we needed to get were located north, across the water from Bowmore, in the town of Port Charlotte just down from Bruichladdich. We were headed out that way for dinner anyway, meeting with a friend from the distillery, so we saved these two for last.

There's quite a bit left from the old Lochindaal distillery, as the old buildings are still in use by local businesses in the town. This one looked the most romantic however, so that's the shot we're using!

Lochindaal Distillery (aka 'Port Charlotte & Rhinns) - set 1829 - Lochindaal was a purpose built distillery in the Rhinns of Islay which survived in the 20th century. Located in the heart of Port Charlotte village, it was constructed for its first licensee, Colin Campbell, in 1829. He held onto it for two years and subsequently it had many owners. It was eventually taken over by Bowmore Distilleries Ltd. in 1921 prior to that company's acquisition by the DCL (early Diageo). That signaled the end of Lochindaal and it closed in 1929. (One of the first of many Diageo closures to come!) Some of it was used by the Islay Creamery until the early 1990's and the shore-side warehouses remain in use by a local garage and the Islay Youth Hostel and Field Centre, while a roadside building is now used for vehicle repairs and the distillery cottage is still inhabited. The bonded warehouses on the hill behind the distillery site have been in continuous use by other distillers and are currently used by the Bruichladdich Distillery. This is the one defunct distillery on Islay that has a good photographic history, which clearly records the distillery site during its century of operation.

Just up the hill from Port Charlotte is the Octomore farm, once the site of an old distillery and the current source for Bruichladdich's proofing water. Bruichladdich has whiskies called both Port Charlotte and Octomore, in tribute to these two former sites.

Octomore Distillery - est. 1816 - This farm-scale distillery on an ancient site behind Port Charlotte was run from 1816 until 1840 by the Montgomery family and licensed to George Montgomery. It appears to have operated as a single-still distillery with a wash still of 60 gallons volume with 998 gallons of spirit produced in 1817-18, which rose to 3,551 gallons in 1826-27. Little is known about its operation until the death of George and his brother around 1840, when it fell into disrepair and the lease was eventually relinquished to the laird, James Morrison in 1854. Buildings on the farm remain today, although some have fallen down and others have recently been converted into holiday cottages, so guests could well be sleeping with the spirits of 160 years ago. No detailed plans of the distillery buildings have yet come to life.

Fraser's notes at Kilchoman also talk about a few other distilleries that were not located on the map, just listed by town name:

Other Islay locations thought to have operated as licensed distilleries include: Ballygrant (1818-21), Freeport (c 1847), Glenavullen (1823-32), Octovullin (1816-19), and Upper Cragbus (c 1841).

As far as we know, these are the lost distilleries of Islay that were actually registered as distilleries. History shows, however, that more than 200 people had been fined for illegal whiskymaking during the 1800's, so obviously there was a ton of action on the island.

Well, I hope that was somewhat enjoyable. That's the best we could do in the time allotted for visiting, and I've typed up all the info as fast as my fingers would fly. I had a good hour and a half on the ferry to do most of it and now I'm at the desk in my Glasgow hotel room finishing it up. Thanks to Kilchoman for letting us use the information and to Graham Fraser who hopefully won't mind either (I'll take it down if you do!).

Tomorrow we meet with Rachel Barrie to look at some Glen Garioch casks before heading out to meet with a new bottler. See you all tomorrow!

-David Driscoll