Kentucky: Day 2 – Bardstown

If you drive about an hour southeast of Louisville you'll find the hamlet recently voted America's Most Beautiful Small Town: Bardstown. Practically all the houses in the area are charming, the main street is like a Norman Rockwell painting, and the whole experience just makes you want to duck into some small coffee shop for a mug of hot chocolate – especially with the cold wind blowing as it did today.

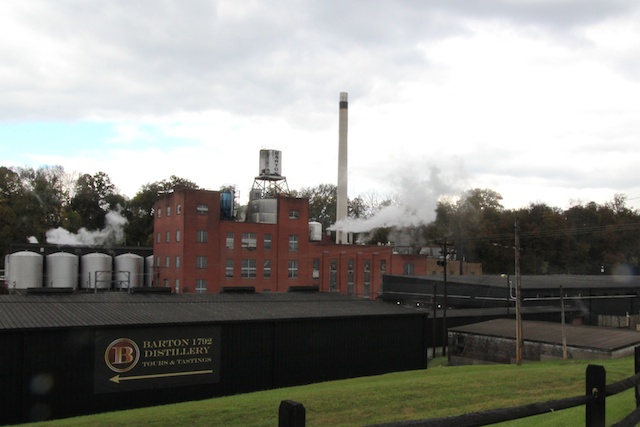

Besides being one of the most picturesque small towns in the country, Bardstown, Kentucky is also home to three of the state's most important whiskey producers. One of them is Barton Distillery, known today as 1792 Ridgemont Reserve. We didn't have time to do much at Barton other than snap this photo, however.

The second, and largest of the them, is Heaven Hill. Twenty-two of Heaven Hill's rickhouses (each holding anywhere from 22-25 thousand casks and with new ones storing up to 100K) are located in Bardstown, along with their insanely large and jawdroppingly-complex bottling line. The entirety of the distillation process, however, takes place in Louisville at the Bernheim distillery. This has been the case since 1996 when Heaven Hill's Bardstown facility was gutted by a gigantic fire that sent rivers of flaming Bourbon pouring down the property's hills. A grizzly fatal car accident two years earlier had already dampened the location of the stillhouse for the Shapiras, the family that owns Heaven Hill, but the fire sealed the deal in their minds. They would not rebuild a new distillery at Bardstown.

Looking at the black residue that covers the walls of the various rickhouses, you're instantly thinking about black soot and other possible remnants from that tragic inferno. However, the black substance that grows on a warehouse wall is mold feeding off the the sugar content left from the evaporating alcohol. As the water evaporates from the aging whiskey it carries with it some of the sweetness from the oak maturation. When the water dries it leaves just a bit of that sugar content on everything in the area, which provides a food source for the black-colored mold. That's how law enforcement spotted bootleggers during Prohibition years – by looking for black trees or black buildings (or a hill full of black maples). That was a sure sign that whiskey maturation was happening nearby.

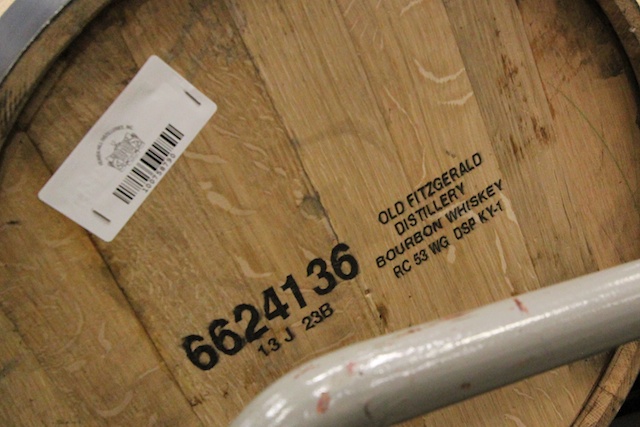

When we decided to visit Heaven Hill's Bardstown operation, we were obviously coming to taste whiskey and take a tour of the facility. However, I'm not sure that any of us were prepared for the size and scale of what we found waiting for us. While Heaven Hill is still a family-owned, family-operated company, it's a huge spirits producer. So big that their one million-plus barrels (yes, more than a million whiskey casks) of Bourbon only account for 18% of their overall business. The bottling line is fully-mechanical and looks like something out of the opening intro to Laverne and Shirley. The Bourbon-filling line (pictured above) can pump up more than 1,000 barrels a day.

We learned a bit about barrel-coding at the filling station. The 13 stands for the year the barrel was filled. The J stands for October (tenth letter in the alphabet, tenth month in the year) and the 23 stands for the day of the month. DSP KY-1 stands for Bernheim – the distillery at which the whiskey was produced.

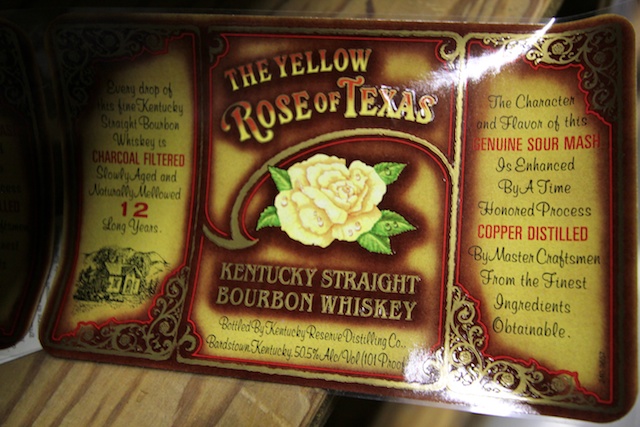

I think our favorite room at Heaven Hill by far was the label room – stacks and stacks and stacks of packages filled with labels for the hundreds of various vodkas, fruit spirits, and liqueurs made by the spirit giant. 82% of what Heaven Hill does is inexpensive booze. But they do make a whopping 86 different Bourbon brands! EIGHTY SIX! That blew my mind. We're used to Elijah Craig, Evan Williams, and Larceny at K&L, but when I started going through the labels there were many names unfamiliar to us out in California. Daniel Stewart?

Kentucky Gold?

The Yellow Rose of Texas? There were so many I could barely keep up.

Some brands, like Mattingly & Moore, were names of former distilleries in the area that had since closed down and stopped producing. Heaven Hill had purchased the rights to the brand name, however, and continued to make the whiskey for those in the area who supported it. Some brands continued on with production despite their relatively small profit percentages. Rittenhouse Rye, for example, apparently costs Heaven Hill more to make than what they sell it for wholesale, due to the higher costs of rye grain today. Sticklers for tradition, however, they continue to produce it because they don't like to raise their prices on value brands if they don't have to. Despite the one million casks being aged by HH in Bardstown, they were still running short on a number of brands – particularly the more mature selections. We were informed that Elijah Craig 18 would be making a return in a few years, but at a much higher price point.

With so many products being made at Heaven Hill there's a lot of people working in the facility and a lot of action going on around you at all times. It's almost overwhelming.

Despite all the fun we were having in the bottling plant, we had come to Heaven Hill for the Bourbon, so it was time to get out to the warehouses and start popping bungs. The crazy thing about HH is that, for all the different brands they make, they only do two different Bourbon mashbills: one wheated formula and one with rye. That means that all the different flavors that make up the different labels come from age, proof, and maturation. There are so many variables that can affect the flavor of a particular barrel: which floor it was aged on, was it near a window, which warehouse did it come from? These are all factors that Heaven Hill keeps a detailed watch upon.

We started with the Henry McKenna barrels before moving on to Elijah Craig, and eventually the Evan Williams single vintage selections. We found two dynamite casks that were no-brainers: one super high-proof Elijah Craig that was very dark and full of richness and a spicy Evan Williams that brought a lot of sweet wood on the finish. We left very happy with our selections.

Then it was on to Kurtz's for lunch where we actually ran into Heaven Hill owner Max Shapira. He's a really nice guy and we talked with him a bit while we ate. I think there's been some form of gravy on everything I've eaten in the last 24 hours.

Just across the way from Heaven Hill, with the rickhouses off in the distance, sit two old corn silos that mark the way to Kentucky Bourbon Distillers and the newly-rebuilt Willett distillery. Long known for their sourced-whiskey-brands like Noah's Mill, Rowan's Creek, and Johnny Drum (along with Willett, of course) the Kulsveen family is finally distilling again after a long, long stoppage.

I wasn't sure what to expect when we pulled up to the new complex, but I can tell you that I definitely didn't expect an operation on the size of what we found. They're filling 22 new barrels a day at Willett and they've already got more than 6,000 casks filled of their own new-make whiskey. Since January of 2012 they've been firing away and we all couldn't have been more impressed with the design, the interior, and the quality of the revamped distillery.

The Willett distillery, despite being entirely remodeled and renovated, is not a new distillery. It was originally founded in the mid-1930s by former Bernheim superintendent Thompson Willett, whose father was once co-owner of the nearby Barton distillery. When Thompson was 27 they decided to build their own facility and in 1937 the first barrel was filled. Subsequent Willett generations would become less interested in the business and decide to get out of the Bourbon game, but in 1984 the old site was purchased at auction by Evan Kulsveen, a hard-working Norwegian who emigrated to America and had married Thompson Willett's daughter. He was looking to bring back his father-in-law's once great operation, but he would first need some money. Apparently Evan Kulsveen is not the kind of guy who takes out loans.

Almost thirty years later, after decades of building relationships and selling other people's whiskies, Evan Kulsveen has finally achieved his goal. They're up and distilling at Willett once again and the smell of fermenting corn is in the air. They've got eight big tanks to cook in so there's plenty of potential in the new set-up.

While they're fermenting again at Willett, they're not using mashbills commonly seen throughout the industry. They've been dipping back into Thompson's old notes, digging out four old recipes – one of which is 72% corn, 13%, and 15% barley. It's not often you see more barley than rye. They're also not distilling the same way as other producers. Willett Bourbon is actually double-distilled on two different types of still. Kulsveen's son-in-law Hunter Chavanne showed us the first run on the towering column still, which produces a white dog that tastes much like other Kentucky producers.

The second run, however, is done on the old Willett pot still and results in a softer, more elegant style of white whiskey. It's very different than what any other American whiskey producer is currently doing and it seems to be working very, very well for the Kulsveens.

There are six warehouses on site at Willett, one of which is entirely full of 6,000 new Willett whiskey barrels. The buildings have been there since the 1930s and are mostly full of whiskey from other distilleries. This one, however, was entirely from Willett.

While Willett has basically put the kibosh on their single barrel program ("Once we got down to only 200 barrels in storage we knew we needed to put the brakes on," Hunter said), there are still a few gems available for purchase at their excellent gift shop. Like this 25 year old rye at 100 proof from a single barrel. Yum.

Before leaving Bardstown we had to go and find David OG's great-grandfather's distillery, of course. Max Shapira said it was now a Heaven Hill-owned site, but he gave us directions on how to find it. I don't think we were supposed to walk on to the property, but how could we deny David this opportunity?

I'll let him tell you about that, however. I'm pooped. That was a lot of typing.

-David Driscoll