Kentucky: Day 3 – Lawrenceburg/Frankfort

Full disclosure here: I am a big Four Roses fan. I love the whiskey. I love the man who makes it: Jim Rutledge. I love everything about the way they do business. They're the only distillery in Kentucky that will bottle single barrels at cask strength for K&L private selections and they have impeccable customer service with their retailers. Needless to say, I was very excited to finally get a chance to see the distillery and take a tour with Jim. We arrived on a cold, cloudy morning and quickly rushed inside to escape the chilly wind.

Jim Rutledge is one of the most knowledgeable and friendly distillers in the business, but that doesn't mean he's without strong opinions. He's very clear about what in his mind constitutes a quality Bourbon whiskey. While he admits that the recent Four Roses Limited Edition Small Batch is one of the best whiskies he's ever tasted, he doesn't think the outstanding flavor had anything to do with the maturity. You can see from the above diagram that Jim firmly believes Bourbon tastes best in between the six and eight year old age gap. In fact, although the current 2013 FRLESB whiskey is a marriage of 13 and 18 year old casks, he claims he was very close to approving a different marriage using much younger stock. "It's not about the age," he said. "It's got nothing to do with that." I absolutely love that he's passionate about spreading that message. It means a lot more coming from him.

Having worked decades for Seagrams, and eventually through Kirin's takeover of the Four Roses brand, Jim has done and seen it all. He watched Seagrams ruin the Four Roses name, turn it into cheap blended "rotgut," as he calls it, and eventually bankrupt itself in the end (he still keeps a momento of the Seagrams LDI blend on his office mantle as a reminder). The reputation of Four Roses as a Bourbon brand after Prohibition was in very good standing. During that period you could still get a pint of Bourbon every ten days if you had a doctor's prescription and one out of every four "patients" chose Four Roses as their "medicine." When the ban was lifted Four Roses quickly became the nation's top brand. Seagrams made its fortune by purchasing Canadian whiskey during Prohibition and amassing an arsenal, ready to unleash at the right moment. Once the ban on alcohol was lifted, they became an overnight giant in the industry. Four Roses was better known than Seagrams, however, so the Bronfman family set their sites on acquiring the name. Decades later after doing so, the Four Roses reputation was in the toilet and the brand wasn't even being sold in the country where it was made.

For years and years Jim attempted to persuade Seagrams to focus on making Four Roses Bourbon again, rather than blended whisky. Ironically enough, the whiskey being made at the Frankfurt distillery went into Seagrams VO, while the LDI and Maryland distilled spirits went into the Four Roses blended. It wasn't until Jim proposed making a whiskey under a different name, say Bullitt County Bourbon, that Seagrams perked its ears. Unfortunately, they soon discovered that the name was too close to another trademarked brand by a small producer named Tom Bulleit, who was contracting his whiskey from Buffalo Trace. Rather than come up with a new name and use Jim's experience and ingenuity to create a new and exciting whiskey, Seagrams spent the money to buy out Tom Bulleit's brand instead. Eventually, Seagrams own misteps ran the company into the ground and Kirin bid for the available Four Roses brand and distillery. Diageo soon picked up Bulleit and Jim was free to get back to work on rebuilding the Four Roses Bourbon brand in America. In 2007, he walked into K&L and tasted us on his first creations. We've never looked back since.

If there's one person to help talk you through distillation, it's Jim. Here we were yesterday thinking that Willett's column still to pot still process was an anomaly in the Bourbon business, but it's not. It's just that no calls the second part of Bourbon distillation a pot still – they call it a doubler (but really it's just a pot still, as you can see). The beer goes into the beer still (or column still), which was pictured in the previous photo, at about 8% ABV while steam pushes through a series of plates that will eventually strip the alcohol to 65% when it reaches the top. It's then condensed into the "doubler" and increased to around 70%. This is why we need to visit the actual distillery of each brand we sell. You think you understand something, explaining it to customers day-in and day-out, until you find out you really don't totally grasp it. I didn't, at least.

Whereas some producers focus on distillation and others on barrel maturation, yeast seems to be Jim Rutledge's biggest passion. He's as excited about yeast and it's potential to create great tasting Bourbon as anyone I've ever met in the industry. Four Roses is renowned for using five different types of yeast and part of the reason goes back to the old Seagrams days. Seagrams had a research and development department totally dedicated to exploring the effects of different cultures in spirits distillation. This was partially because they would purchase a brand, but close the distillery where the brand had formerly been made (Henry McKenna, for example, which had been made at Fairfield distillery). Rather than operate an entirely different plant, they would use different yeast strains to create different flavors to help separate their newly purchased brands – a practice that was carried over to Four Roses.

Today there are five different yeast strains fermenting in giant red cedar vats at the distillery. There are also a few stainless steel tanks as well. Jim is a stickler for making sure the mash cook and fermentation process have taken place correctly. If the spirit doesn't taste right coming off the still, they'll discard it and sell it off to a rectifier for vodka. They have a panel to decide whether or not a spirit is worthy of going into barrel. If they vote down a batch of distillation it's $30,000 worth of profit they're losing. Jim says this can happen almost every day. In order to keep things fresh, Four Roses creates a new strain of yeast culture every single week. Compare this to other distilleries that are dumping enzyme formula and bags of dry commercial yeast into their tanks with each cook and you'll really start to understand how seriously JR takes his whiskey.

The Four Roses warehouse buildings are not at the distillery site, so we decided to come back tomorrow to do barrel sampling at the Cox facility. In the meantime, however, we were starved. This place looked amazing from the highway. And it was. Mmmmmm.......pulled pork with cole slaw and baked beans.

Buffalo Trace distillery is like something out of Upton Sinclair's The Jungle or a scene from an old mobster movie. We were waiting for trenchcoated men with tommy guns to step out of a side alley at any moment. Much of the distillery, formerly known as George T. Stagg, was built in the late 1800s and is like a functioning museum. Much of the equipment onsite hasn't changed since Prohibition and the huge campus, about 100 acres, seems like a Hollywood studio. It's really a sight (and site) to see.

Every building is made out of red brick and no matter where you look there's steam coming out of some pipe or window. It looks absolutely amazing against the stark grey sky.

Walking through the distillery's innards is like moving through the inside of an old U-boat or some contraption from the Henry Ford museum. Staircases lead up through metal casings as smoke piles out of vents in the floor. I really couldn't get enough of it.

Buffalo Trace's beer still is like a rocket silo. It's absolutely huge! It towers up several stories and really manages to crank out some serious distillate.

Their "doubler" is nothing like a pot still, but rather like an Apollo moonrover.

They also have this giant thing outside called a "kettle" still that they sometimes use to finish off their Rain vodka. I'd never seen anything like it.

There's also a distillery within a distillery at Buffalo Trace. Harlan Wheatley had this little experimental pot still installed a while back and the room was named the "Colonel Taylor Jr. Distillery" – a place where they can play around with things like rice and oats without having to take time away from their normal production. This is also the still that ran 159 times to create the Clix vodka. Can you imagine having to do that 159 times?

Of course we raided the warehouse to find some tasty Buffalo Trace samples. The shortage of whiskey is no secret at the distillery. There's nothing in the gift shop besides 1.75L bottles of Buffalo Trace, Rain vodka, and the Bourbon Cream. No Weller, no Eagle, no Elmer, no Blantons....nada. They're totally wiped out for the year. We did find some tasty BT selections, however.

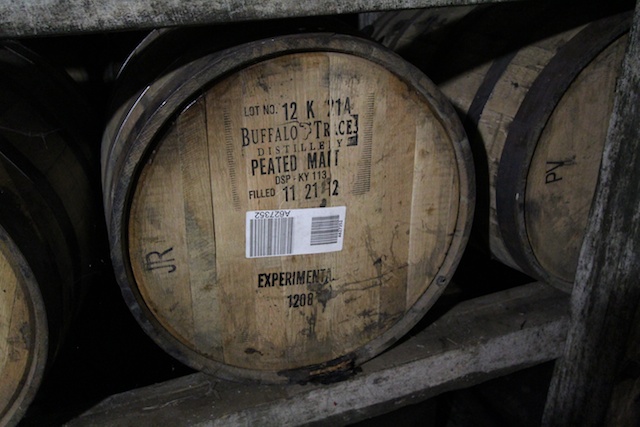

And what the heck is this? Peated malt whiskey from Buffalo Trace? Yikes! Can't wait.

That's it for today!

We've got a lot to do tomorrow in a very short amount of time.

-David Driscoll