Understanding Vodka – Part I: Polish Tradition

First off, let me start by saying that this week's effort to understand vodka is not an attempt to reach out to whisky drinkers to help them crossover into an appreciation of this great white spirit. There are few whisky analogies in this article because vodka is not whisky. I'm writing these articles in an attempt to increase my own understanding (and therefore appreciation) of vodka because I like to drink and I like to know why others like to drink, too. Therefore, if you're totally bored with vodka and have no interest in learning more about it, you'll need to find another blog to read this week because I'm not drinking anything else besides vodka until Sunday, therefore I won't be discussing anything else besides vodka until Sunday.

That being said, let's get to it!

If you're going to start a conversation about vodka (which I am attempting to do), it makes sense to start with Poland. I know many people consider Russia to be the motherland of vodka distillation, but vodka as we know it has been produced in Poland for more than 600 years and it's believed that vodka originated there (it's a scholarly argument that's open for debate, so I won't definitively say anything here). I will quote a Wikipedia site, however, so that you can have something to chew on:

Scholars debate the beginnings of vodka and it is a problematic and contentious issue due to little historical material available on the subject of the origins of the drink. According to some sources, first production of vodka took place in the area of today's Russia in the late 9th century; however, some argue that it may have happened even earlier in Poland in the 8th century. According to the Gin and Vodka Association (GVA),the first distillery was documented over three hundred years later at Khlynovsk as reported in the Vyatka Chronicle of 1174. For many centuries, beverages differed significantly compared to the vodka of today, as the spirit at that time had a different flavor, color and smell, and was originally used as medicine. It contained little alcohol, an estimated maximum of about 14%, as only this amount can be attained by natural fermentation. The still allowing for distillation – the "burning of wine" – was invented in the 8th century.

There is evidence of large-scale distillation in Poland by the end of the 1500s. It wasn't anything modern or advanced like we have today, but it was happening and rye was the grain of choice. According to the same Wikipedia article, Jakub Kazimierz Haur, in his book Skład albo skarbiec znakomitych sekretów ekonomii ziemiańskiej (A Treasury of Excellent Secrets about Landed Gentry's Economy, Kraków, 1693), gave detailed recipes for making vodka from rye. At Polmos Zyrardów distillery, west of Warsaw, they've been producing vodka since 1910 using only Dańkowskie Złote, a strain of rye that has been cultivated and farmed for centuries within the soil. Polmos Zyrardów is where Belvedere vodka is made today and it is distilled only from this locally sourced grain. The distillery has a pretty detailed history as well. I could tell you about it, but I would only be paraphrasing the information I've recently received from LVMH, so why not just let them tell you? I hit LVMH up for a TON of information today, basically grilling them on anything I could think of. The following is the result of those queries:

Belvedere Vodka hails from the small town of Żyrardów in the Mazovian plains of central Poland, 45km west of Warsaw at the Polmos Żyrardów distillery. The quiet lane which leads to the distillery runs parallel to the tracks of the original 1845 Warsaw‐Vienna railway. Pronounced, ‘Chu‐Rar‐Doff’, Żyrardów was a key industrial town at the time the railway was constructed, so was connected with its own station. With its fairy tale architecture, this cute little station still stands on the opposite side of the tracks just minutes before you reach the distillery.

The past industrial importance of Żyrardów owed much to Philippe Henri de Girard, a French engineer who invented a linen spinning machine. He patented frames for dry‐ and wet‐spinning of flax in Paris in 1810. Girard was responding to Napoleon I’s offer of a one million franc reward for such an invention as he sought to stop English cotton fabrics entering continental Europe. Napoleon reneged, so Girard sought his fortune in England and in 1815 also patented his invention in London where the Industrial Revolution was in full swing. His move coincided with the Battle of Waterloo, so as registration of the patents under a French name would have been problematic, he used the very English sounding pseudonym, Horace Hall.

In 1825, Girard was hired by the Polish government to help develop its textile industry. Backed by the Bank of Poland, in 1831, he established a factory in Marymont near Warsaw. Two years later he moved to the village of Ruda Guzowska in the Mazovian plain (Nizina Mazowiecka, or Plains of Łowicko‐Blonska) where the Łubieńscy family owned vast tracts of land ideally suited to growing the flax that linen is spun from. Two brothers from this family built Fabryka Wyrobów Lnianych, the largest linen factory in Europe, and hired Girard as their technical director.

In 1857, the factory was bought by Karl August Dietrich and Karl Hielle, two German entrepreneurs who expanded the factory and built an industrial town around it. The main square was opposite the factory gates and bordered by civic buildings such as the town hall, library, school, nursery and the imposing Holy Mother of Consolation Parish Church. Around this central hub, lines of terraced housing for the weavers and labourers were constructed. The huge factory, civic buildings and the houses were all built from locally made red bricks.

By 1900, what was a small village had turned into a large industrial town of 30,000 people. The rapid growth and affluence of Ruda Guzowska and its connection to the Warsaw‐Vienna railway attracted bakers, brewers and other trades. Ruda Guzowska also became a popular place for displaced Jews to settle, including two Russian brothers called Pine, who in May 1910 opened their distillery, now Polmos Żyrardów – renamed in honour of Girard after the Polish spelling of his name – on the edge of town. Żyrardów is now a uniquely preserved 19th century industrial town with efforts underway to attain UNESCO World Heritage status. The town retains a reputation for its fabric and the Linen Fabrics Żyrardów Company continues to operate in the grounds of the former linen factory. The old linen factory still dominates the centre of town and is being redeveloped as an apartment building. Today, however, Żyrardów is better known for making vodka. Belvedere’s strip stamp honours this history by reflecting the colour of the flax flower, the plant from which linen is spun.

That's a pretty cool story, right? But what does that have to do with how the vodka is made or how good it tastes? Don't worry, I've dug up the specifics. What I want to make clear before I explain the process is that I've never been to a distillery that actually distills its own vodka. I've been to distilleries that rectify vodka, meaning that they purchase inexpensive neutral grain spirit and redistill it to purify it further (which is what many American vodka producers do), but I've never seen anyone actually start the process by fermenting their own rye, wheat, or corn and make vodka out of it. It's not a process that most modern distilleries can handle because it's quite an agricultural process. Think about the grain whisky component of Scotch: how many grain distilleries are there? Not many, and there's a reason why: it's much cheaper to do it on a large scale. Belvedere does not ferment their own rye either.

The "agricultural" distillation, the initial fermentation and first distillation, takes place at ten agricultural distilleries who work in partnership with Polmos Żyrardów. These farms plant the grain in September and start harvesting the Dańkowskie Gold and Diamond rye in late July the following year, finishing around a month later. They then store the grain for distillation over the following eleven months of the year. According to Belvedere, by the end of the communist era (1989) there were some 900 working agricultural distilleries in Poland but now only some sixty survive, but those left are far more technically advanced and produce more alcohol than the 900 inefficient state‐run distilleries did.

To quote my information from Belvedere further:

After harvesting, the Dankowskie Gold rye is simmered in a vessel, which is basically a vast pressure cooker, to form a mash resembling a thick porridge. Amylase and diastase enzymes are added to aid the breakdown of starches into sugars and so speed the fermentation. Distillers’ yeast is added and the resulting fermentation produces a beer‐like wort at 7‐8% alcohol/volume. This is distilled in a column still to produce raw rye spirit at 92% alcohol/volume which is shipped to Polmos Żyrardów. Organoleptic and chemical analysis of samples submitted by these agricultural distillers enables Polmos Żyrardów to ensure they receive raw spirit of the highest quality.

So as you can see, the production of vodka is more about taking high-proof grain spirit and rectifying it. Whereas many distilleries I've visited simply purchase their NGS from the general market, sometimes knowing little about its origin, Belvedere (and many Polish vodkas for that matter) works closely with both the farmers and the agricultural distilleries from which they contract.

What makes the rye so important if it's being distilled so many times?

If you're a skeptic like me, you'll wonder what exactly makes this Dańkowskie rye so important if the final result is going to be a neutral spirit anyway. There are actually two forms of this grain: gold and diamond, and they work differently in distillation. Maybe even more important is the way they affect the ultimate flavor of the vodka. Here are the details:

Dankowskie Gold Rye - A unique strain of winter rye cross cultivated over 100 years and only grown in the Mazovian plans of western Poland. This grain is cherished for its usually high starch content (around 65% vs. the standard 50‐55% for generic rye) which makes it perfect for distillation. Winter rye is any breed of rye planted in the fall (late August/early September) to provide ground cover for the winter. It actually grows during any warmer days of the winter, when sunlight temporarily brings the plant to above freezing, even while there is still general snow cover. This means that rye is climatically the perfect grain for the colder climates of Poland eastern Ukraine.

Rye is a rich and complex and grain which has a wide range of flavour characteristics depending on

fermentation and severity of distillation. It is not uncommon to find aromas of butterscotch, fudge or

toffee, and flavours of toasted rye bread, cream or white and black pepper within a high quality rye

vodka. The skill lies in the distillers ability to draw out the positive characteristics of the grain. In terms of the raw material hierarchy, rye tops the list due to its comparative scarcity when compared to other grains, and Dankowskie Gold rye is only grown successfully in Poland making this the most a highly prized Polish grain.

Dankowskie Diamond Rye (used in the Belvedere Unfiltered only) - First registered in 2008, Dankowskie Diamond Rye is a rare, baker’s grade rye that only grows on a hand full of Polish farms. The grain has a a low starch content and distinctive characteristics not normally associated with rye grain. Through Polmos Żyrardów's Raw Spirit Programme, Dankowskie Diamond Rye’s potential as a distilled grain has been unlocked. Working closely with select agricultural partners and the University of Lodz, Dankowskie Diamond has been carefully grown and fermented and distilled in order to maximise the unique characteristics of the grain. For this reason, the decision was also taken to leave the Vodka unfiltered, to preserve the exceptionally viscous mouth feel and soft, delicate flavours coming solely from the grain.

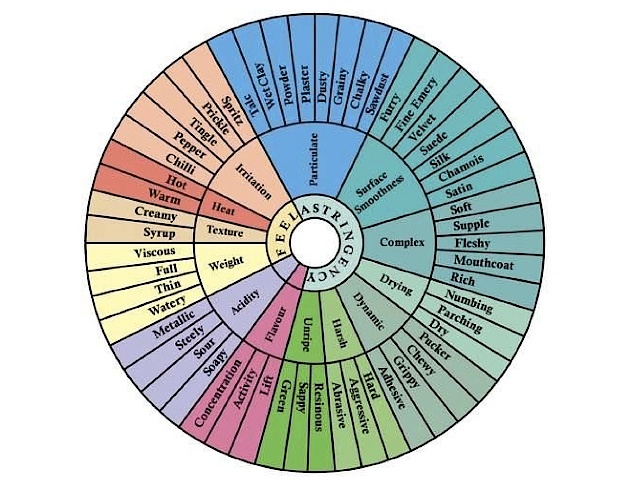

Belvedere's vodka flavor wheel - just like whisky!

Belvedere's vodka flavor wheel - just like whisky!

When you taste Belvedere, or even other Polish rye vodkas, next to a wheat or potato vodka, there is indeed a difference in both the flavor and the mouthfeel. I was actually shocked to find that Belvedere created a flavor wheel, much like the ones you find with whisky, to explain what one is tasting (very helpful, by the way). I found that in a blind tasting next to other non-rye, non-Polish vodkas, my wife and I chose both the Belvedere and Potocki vodkas as our favorites. They were both clean, soft, creamy, and pure as they finished. Coincidence?

What makes the water so important?

If a grain is being distilled until it is technically neutral in flavor, then the water used to proof down the spirit will play a big role in the ultimate purity of that flavor. Here is the information on Belvedere's water procedures:

Polmos Żyrardów has its own two artesian wells from which it sources all the water used in the distilling process. These wells are constantly monitored by security systems and not shared or used for any other purpose other than the production of Belvedere Vodka. The artesian well‐water passes through an eleven‐step purification system which includes reverse osmosis to remove all dissolved salts, such as sodium, chloride, calcium carbonate and calcium sulphate. The aim is to produce pure, tasteless water, which will not affect the flavour of the finished vodka and will act as a blank canvass for the Dankowskie Gold or Diamond Rye to be expressed. Without this pure, soft water the elegance of the vodka would be reduced and it is therefore integral to the flavour delivery and mouthfeel of Belvedere.

Water represents 60% of a bottle of Belvedere, the quality and consistency must be assured. This is why the land we draw the water from is owned and protected and the water source itself is not mechanically aided. This ensures the water delivered to the distillery in an entirely closed, acid resistant stainless steel pipes is as unadulterated as possible. A premium water source is only part of the equation when it comes to producing a premium spirit, particularly for vodka. A water that is pure, soft and unadulterated that is used to emphasize a premium distillate suggests that the spirit in question is something worth emphasizing.

I found that to be a great explanation. There's no hiding the fact that water makes up "60%" of the bottle, so it's an incredibly important ingredient. On the flip side, this is a statistic that is usually used to mock vodka as a spirit worthy of connoisseurship. It all depends on your point of view, I guess. Although if you travel to Scotland and visit the distilleries, you'll hear a lot of talk about the importance of Scottish water there as well.

What is the rectification process?

I was impressed by how clearly LVMH discussed the rectifcation process as well – the means by which the vodka is purified through further distillations. Most interesting is the fact that the spirit is dilluted with Polish water before it's distilled again. Check out this piece of info:

After a stringent chemical and organylipical analysis, the raw rye spirit from the agricultural distilleries is brought into Polmos Zyrardów and diluted to 45% alcohol/volume using the purified water. It is then distilled and rectified using a three‐column process with a capacity of 23,000 litres per day. Firstly a 250,000 litre pre‐distillation column removes acids, esters and aldehydes. A second rectification column removes the remaining fusel oils and produces a spirit at 96.5% alcohol/volume. Finally, a third purifying column removes any remaining off notes or odours from the spirit: hence the claim that Belvedere is “quadruple distilled”, once at the agricultural distillery followed by the three‐column process at Polmos Żyrardów. The pure spirit is stored in tanks for a minimum of two days to allow the spirit to rest before being hydrated to bottling strength with the distillery’s own purified artesian well water. This marrying process takes place slowly over several days. The vodka then undergoes filtration through activated charcoal and cellulose particle filers prior to bottling. The whole Belvedere production process is designed to produce a very pure spirit that still retains character: Belvedere is distilled and filtered just enough to retain all the character of Dańkowskie Gold or Diamond Rye.

One thing about Polish vodka that makes it interesting is that it is one of the most regulated types of spirit in existence. As a distiller, you can't legally buy cheaper rye from Russia or China, import it in, and make Polish vodka. All of the base materials (either rye, wheat, or potatoes) must be Polish, the water must come from Poland, and the product must of course be distilled in Poland. European law also recognizes Polish vodka as having its own geographical appellation, further stating that it may not have further additives besides water (this does not count for "flavored" vodka, of course, which is its own category). Belvedere is just one of several outstanding Polish vodkas we carry at K&L. Potocki and Chopin (made from potatoes) are also quite good. But, of course, they've been making vodka in Poland for centuries, so you'd expect that right?

There is a tradition of drinking and distilling vodka in Eastern Europe and it definitely shows when you compare their products next to vodkas from American and elsewhere. Maybe it's because they take it more seriously? Maybe it's because they're not rolling their eyes and holding their breath as they make each batch, knowing that it's just a way to make money while they're waiting for their whiskey to age?

We'll see! More vodka information coming later.

-David Driscoll