Canadian Whisky: A Primer with Davin de Kergommeaux

Esteemed Canadian whisky historian and critic Davin de Kergommeaux

Esteemed Canadian whisky historian and critic Davin de Kergommeaux

I've been trying to break into Canadian whisky for the last few months, but I've been side-tracked by numerous other projects, a lackluster interest in the subject from my consumers, and a general apathy from distributors to get me samples of new Canadian items. Canadian whisky is simply not getting the rub from its big brothers Scottish single malt and Kentucky Bourbon right now; at least, not at K&L it isn't. A number of recent experiences, however, have instilled a new passion in me to discover more about our neighbors to the north. One of the most inspiring visits I had in years came when John Hall, the owner of Forty Creek, came by the store this past October to share his products. Not only were the whiskies delicious, but the information that accompanied them also fascinating. I was intrigued. The Forty Creek expressions were exciting in the way that a mature Bordeaux wine is exciting; they were subtle, haunting, and complex.

Over the past few months, I've been reading both a book and a blog written by Davin de Kergommeaux: the man who has become the leading expert on Canadian whisky world-wide. I've been scouring his reviews, hoping to find interesting and unknown products to taste or learn about, while researching the available selection here state-side. With the arrival of a few new Canadian releases imminent, I thought now might be a good time to continue my interview series here on the blog and sit down with Davin to get his thoughts on the new Canadian renaissance. There are many misconceptions about Canadian whisky, reasons that the genre still fails to get the respect it deserves, and Mr. Kergommeaux was more than happy to help put these rumors to rest. I learned a great deal in the thirty minutes we talked; so much that I thought it might be of interest to you readers as well. Check out our conversation below:

David: You’ve become the go-to guy when it comes to Canadian whisky. Whenever anyone I know has a question about the subject they bring your name up. You’re the Canadian whisky reviewer for the Whisky Advocate, and you’re the person I email whenever a customer asks me a question I can’t answer—and I can’t answer most of them because I know very little about the subject. How did you become that guy?

Davin: Well, I started out with single malt Scotch and I was fairly convinced that that was the only good stuff out there. I kept tasting better stuff, and better stuff, but I live in Canada and I was interested in the history of some of the old distilleries we have here. I would drive by old sites like the plant in Corbyville; I saw that from the time I was a little kid. It’s ripped down now, but that was kind of a landmark on our drives to Toronto. So I got to tasting some of this whisky, and it was delicious. If you didn’t know it was Canadian whisky, you’d say it was as good as anything else. It started to grow on me. I never lost my interest in Scotch—I still love it—and I had started to learn more about Bourbon, some of which were amazing. The love of Canadian whisky crept up the same way, and the more I began to taste different types of whiskies, the more I began to enjoy the subtlety of the Canadian expressions. It doesn’t whack you in the face like an Ardbeg, but as the palate develops you’re able to appreciate more nuance.

I think most people know Canadian whisky best from the mixing or well whiskies they see in the bar. Imagine what the reputation of Scotch would be if the only whiskies we knew were J&B and Cutty Sark. They’re both good whiskies in their own right, but they’re not going to inspire the same type of enthusiasm as say a Mortlach or an Ardbeg. So as I kept tasting, I began researching in the library. I thought that I pretty much understood Canadian whisky at that point because of all the stuff I had read online—the disparaging comments from people who didn’t think it was as good as Scotch—but it turned out that what most people thought was wrong. I got deep into the history, digging through the archives, and it turned out that marketing people were the ones filling in the blanks—the folks who wanted you to think that Scotch was better, or that Bourbon was better. They were the ones dictating the reputation of Canadian whisky.

David: What role do you think Prohibition played in the dubious reputation of Canadian whisky?

Davin: Prohibition killed us. It really hurt Canadian whisky. That’s not actually where it got its reputation; being smuggled in over the boarder. Canadian whisky made its reputation during the American Civil War; three generations earlier. In 1865, Canadian whisky was the top-selling whisky in the U.S. and it stayed that way right up until Prohibition. Of course, during Prohibition Canada ended up importing a lot of Irish whisky, which ended up going down to the U.S., but ultimately the main market for Canadian whisky dried up. There was so much misinformation. People said that Canadians spelled whisky without the “e” because of the Scottish influence at the time, but there were no Scots making whisky in Canada. They were all making rum. But all this information was being taken for granted, so I just kept picking away at it. I would spend all this time in these old archives—stinking like must—at places that might only be open one day out of the week. The more I did it, the more I got into it.

David: How do you feel now that there’s a new resurgence of interest in Canadian whisky, yet at the same time producers are trying to pass it off as American rye? That seems almost like a lack of confidence from certain brands in the progeny of the Canadian whisky bloodline.

Davin: I don’t think they have to disguise it. I think that’s a choice that certain brands have made because of the American interest in American-made things. “Made in America” is very important to Americans. Whistle Pig, for example, did not have to disguise the fact their whisky is Canadian, but they chose to. Masterson’s, on the other hand, did not disguise their source; in fact, they bragged about it. They choose to put their whisky into the Canadian category each year at the whisky awards, for example. Whistle Pig does not. Masterson’s is becoming the clear leader now. Whistle Pig has done a brilliant marketing job, but of course the few hundred people who care about disclosure just trash the company for not disclosing their source—which of course creates controversy and 1,000 new customers for Whistle Pig who don’t care about disclosure.

David: Isn’t that funny how publicity works? (laughs)

Davin: People love to harp on the negatives about Canadian whisky; especially in America. They love to make disparaging remarks—Canada is kind of the butt of a lot of jokes, if you didn’t know. Shanken came out the other day and said that Canadian whisky is struggling to retain its prices and market share. But what they’re talking about is a specific slice of the market share—the low-end stuff. What they don’t mention is that there has been an 18% increase in sales of the high-end stuff. So people tend to take little soundbites and put them together to tell the story they want to tell about Canadian whisky. The truth of the matter is this: every distillery in Canada is expanding. They can’t keep up with demand! Hiram Walker used to operate five days a week. Now they work twelve days straight before taking a break. It all depends on how you look at it. But connoisseurs are beginning to see that quality whiskies are coming from Canada, and now we’ve got writers writing about it. Lew Bryson, Dave Broom—they’re all getting on board, so people are eventually going to discover it.

David: That’s what John Hall from Forty Creek told me earlier this year.

Davin: He told me the same. He said to me: “Canada is always five to ten years behind the U.S. Bourbon is big right now, but you watch—five years from now Canadian whisky will be what everyone wants.” And I believe him. Canadian distilleries have been making great whisky for years, but now they have the confidence to talk about them.

David: John Hall really blew my mind when he was here this past Fall. I tasted those Forty Creek expressions and I was in utter shock. I couldn’t believe how good that Confederation Oak was along with the complex process of making it. I, too, think he’s right. It’s only a matter of time, not just because I think that’s the way trends tend to work, but also because of something you touched on earlier about the development of your palate. In the wine world, where I spend most of my time, that’s the natural progression of things. We all start with big, bold Napa wines—high alcohol and bold flavor—but eventually we move towards France and lower alcohol wines with nuance and complexity. Today, I want delicacy, and that’s exactly what I get from well-made Canadian whiskies. They’re more mysterious, and less obvious.

Davin: And we’ve got those big whiskies; the ones that punch you in the mouth. But we’ve got so many more of the delicate ones. It was a big revelation for me when I went out to the Crown Royal facility and toured the Gimli plant. I found out that all the guys who worked there drank a whisky called Canadian 83—a whisky made with used Crown Royal barrels. When they’re done aging Crown Royal, they ship the barrels to Montreal and fill them with spirit—that’s what they use to make the 83. I asked one of the guys about it, who told me: “Crown Royal takes all of the wood out of the barrel and all that’s left behind is the velvet.” There’s a subtlety and an elegance to Canadian whisky that Canadians tend to like. Like you said about French wine—it’s not from Napa. It’s thinner, but ultimately very complex.

David: How is Canadian whisky viewed in Canada? Is there a similar sense of nationalism like Americans feel for American whiskey right now?

Davin: We don’t have the same kind of nationalism here. We tend to look outside our borders for the best. However, Canadian whisky is the second-highest selling spirit in Canada—just behind vodka. In Canada, this little country we have here, we drink more than 30% of what we make. People here are crazy about rye and ginger, or rye and Coke—we call it “rye” up here—everyone loves it. I just did a tour of Newfoundland and every bar I went to had Canadian whisky on the counter. Go through northern Ontario and it’s all Wiser’s. That’s what they drink. So, yes, Canadians love Canadian whisky, but it’s mostly because it’s readily available, they like the way it tastes, and it’s also pretty inexpensive.

David: What do you think the biggest misconceptions are about Canadian whisky that tend to scare away American consumers?

Davin: I think many people believe that Canadian whisky has neutral spirit added to it. It doesn’t. We hear terms like “brown vodka” tossed around, but try something like Wiser’s 18—that’s a whisky made to a high ABV with full wood flavor. Others think that Canadian whisky is artificially flavored. On blogs, for example, people love to harp on the 9.09% rule—it’s very naive. These are the things people talk about when they want to disparage Canadian whisky—artificial flavorings and things like this. People think it’s always light and simple, but it’s not. There are some very robust whiskies in Canada. But ultimately people like to have something they can dismiss because it makes them feel better about the things they like. Some day, however, the right people are going to start talking about Canadian whisky and these folks are all going to jump on board with them.

David: I’d love to start talking more about Canadian whisky! It’s just that we’re very limited down here. Many of the exciting whiskies I read about on your blog aren’t available in California, it seems.

Davin: It’s not because there’s a lack of a push strategy, but rather a lack of a pull. Distributors need to see a long-term plan in order to bring new products to market. Canadian distillers haven’t been very bold about going after these new markets either. That’s why Masterson’s is doing so well. They’re willing to sell only a few cases, if need be, just to break into a new state. Take Hiram Walker, however, and they’re bottling 500 bottles a minute. They’re not interested in doing small orders. I think they’re making a new effort with the Wiser’s range and Lot 40, Pike Creek, etc. There is a new effort being made. Look at Forty Creek. This is a small distillery, so they can afford to do small orders across the border. I think you’ll see this change quickly with other producers.

David: We’ve done very well with the Lot 40 whisky, but ultimately I think it’s because we have it in the rye section, not the Canadian section. But that’s because we don’t really have a Canadian whisky section and that doesn’t sit well with me. I don’t like people who pretend to be something they’re not, so I don’t like selling whisky by trying to pass it off as something else than what it is. In fact, one of the biggest meltdowns I’ve ever had with a customer came after he realized the Lot 40 was Canadian and not from America. It was a spectacle, to say the least. He went from loving it to hating it in a split second.

Davin: You’re always going to have customers with different expectations. I don’t see anything wrong with calling it rye. It’s made from 100% rye! These are the same people who make silly comments about Canadian whisky due to their lack of understanding.

David: But I find my lack of understanding exciting not infuriating! I mean, that's what makes me want to learn more about Canadian whisky. When John Hall told me that all of the different grains are fermented, distilled, and aged separately—that blew my mind! I immediately wanted to know more.

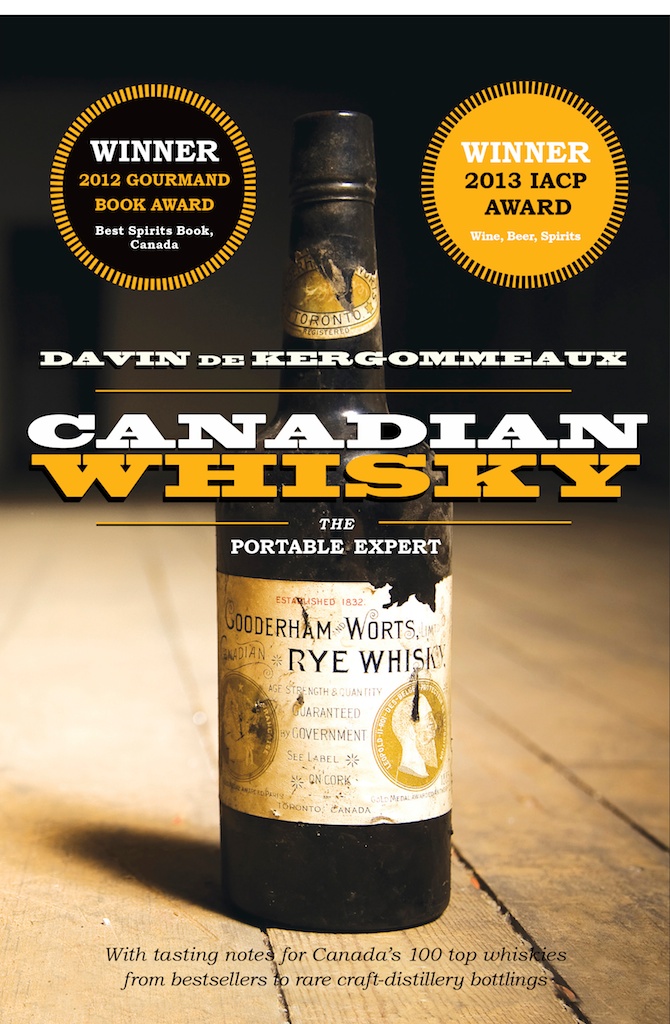

Davin: This is something John does that has been lacking with other Canadian distillers—they haven’t gone out and promoted their product. They’ve been a little bit complacent. That’s part of the reason my book has been so successful: it filled a big hole. You had people begging for this information and there was really nothing there for them. You wouldn’t believe how hard it was to get into some of these distilleries. They were completely disinterested in telling their story. Now they’re beginning to realize that telling their story is an important part of selling their whisky, and now there are marketing departments and PR agents. There are great whiskies out there right now—like Crown Royal Monarch, for example. I think that story is finally starting to get around.

David: What is the story with that whisky?

Davin: It’s the 75th anniversary of the release of Crown Royal in Canada. Crown was a whisky that was originally made in celebration of King George and Queen Elizabeth—the mother of the current queen. Sam Bronfman, who made this whisky from a blend of about fifty different whiskies, he put two cases of this on the train the royals were traveling in when they visited. They were well-known as whisky drinkers at the time. Now there’s no evidence the king and queen actually tasted it, but it was a wonderful marketing tool and he ultimately refused to release it into the states. Now, seventy-five years later, they’ve recreated a new version that’s just loaded with what they call “Coffey rye”. They have a Coffey still in Gimli and they make a rye whisky with it—I think Monarch is comprised of about one third of this. It’s the best tasting Canadian whisky I’ve tasted….probably ever. It’s just fantastic.

David: Wow! Those are bold words!

Davin: It’s as good as Forty Creek Confederation Oak. Maybe Centennial 15 from the 1950s is better, but that’s about it.

David: Well, that’s easy to find isn’t it? (laughs)

Davin: Thanks for catching me on that.

David: Well that’s exciting. But this is a product—Crown Royal—that the average American whiskey consumer wouldn’t bat an eye at, if there weren’t people basically shouting this information at them. And even then I’m not sure they’ll care all that much. I certainly don't think of Crown Royal as falling into the "best whisky ever" category.

Davin: I think you’re right. Canadians are not big about talking about themselves, and they’re fairly self-deprecating, as well. But you’re going to see more talk about Crown Royal over the next year, more about Canadian Club—this new rye they have is spectacular. It’s so delicious. It’s at 40%, so it’s meant for the general consumer, but people are going to be pleased. With Campari buying Forty Creek you’re going to see them go global, So it’s coming, David. And you’re at the cutting edge of this industry, so good for you that you’re getting into this now. I think this will eventually be a big part of your business.

David: I hope it will be. I’m really excited about it, so it makes my job more fun when my excitement crosses over into my business. Canadian whisky is something familiar, but at the same time entirely different. It’s like you said earlier: there are people who are afraid of what they don’t understand, so they dismiss it. To me, however, that’s the exciting part. I’m over the moon that there’s a completely new genre of whisky, with mature stocks, that I know absolutely nothing about and can dive right into. It gives me the opportunity to start all over again, be a student, and get excited like I used to get.

Davin: That’s exactly what happened to me! I’ve tasted some brilliantly sublime whiskies in my life, but it doesn’t mean I don’t enjoy going back to the classics. I think you expressed it better when you talked about old world wines, however. We start with Napa or Australia and we eventually move into the old world.

David: Ultimately, you want to try new things and experience new flavors. I think it’s really about learning how to taste. In that sense, it may be that Canada is five to ten years ahead of the U.S., rather than behind us. They may already have a more evolved palate. We’ll have to see.

Davin: I guess it’s all a matter of perspective, isn’t it?

-David Driscoll