Central Valley Rye Harvest

Some of you might remember my article about Corbin distillery from the five part series I did about vodka last year. But, then again, it was a blog post about craft vodka so you might have just skipped over it. If you don't feel like going back and perusing the details, I'll give you a quick summary: Corbin is a farm located in Atwater, California (just south of my hometown of Modesto in the Central Valley—we had some heated baseball games against Atwater High School) that grows sweet potatoes. A few years back, David Souza—whose family has farmed in the region for a hundred years—decided to add a still to preserve the unused harvest (just like farmers have been doing for hundreds of years) and Corbin Sweet Potato Vodka was born.

However, what I just learned recently (during a phone call with the distillery) is that sweet potatoes need a lot of nitrogen to grow. Therefore, a nitrogen-heavy fertilizer is used to help the soil provide the necessary nutrients for the crop. The sandy soil of Atwater, however, leaches a lot of the nitrogen deep into the earth and a cover crop is needed to help remove some of the nitrogen before another round of sweet potatoes can be planted. It just so happens that rye is the perfect cover. Erik Teague, the brand manager for Corbin, told me:

While sweet potatoes are our primary crop, a hearty, drought tolerant cereal grain, native to California— called ‘Merced Rye’— is planted after sweet potato harvest. Merced Rye not only flourishes in our extreme climates without a high demand for irrigation, it has a very helpful extensive root system. Reaching soil depths of up to thirteen feet, Merced Rye naturally mines nutrients that have leached into our sandy soil, back to the surface. When the stocks are disked back into the ground, it provides a soil base rich in nutrients for following seasons’ crops.

The fact that Merced Rye is a grain we know very well and is in no short supply to us, creates a desirable substrate for us as distillers.

Rye being ground into grist at Corbin distillery

Rye being ground into grist at Corbin distillery

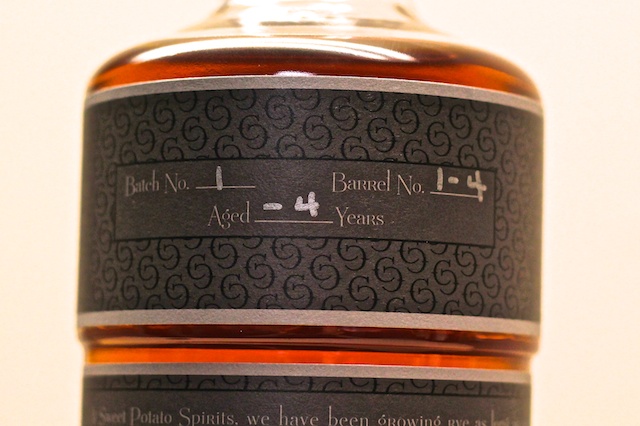

You can guess where this is going. It turns out that Corbin hasn't only been distilling sweet potato vodka over the past few years; they've also been growing, harvesting, fermenting and distilling their own rye—purchasing custom-charred, 53 gallon white oak barrels from Missouri and filling them with their 100% farm-to-bottle distillate. They began maturing their whiskey four years ago and today we finally get to try the finished product. I know my pal Chuck Cowdery will be happy to hear that when you buy a bottle of Corbin Merced Rye Whiskey, it's actually entirely made in the region designated on the label (unlike a large number of other rye whiskies on the market).

It's also not some six-month-old, quarter-cask-aged, rushed-to-market, let's-capitalize-on-the-whole-rye-boom, "craft" whiskey. It's the real deal, and the story is a big part of what makes it so special. I can't think of one other distillery that is handling every step of the rye-making process from literally planting the seed, to bottling the mature spirit. If you care about that kind of thing, you're going to want a bottle of the Corbin Merced Rye Whiskey—especially if you have any California pride! If you don't care about that kind of thing, you're still going to want a bottle simply because the whiskey tastes good.

Corbin Cash Merced Rye Whiskey $46.99 — Distilled on the same German Holstein still, the almost 4 year old rye (3.75 years to be exact) shows a perfectly-balanced nose of rich oak and rye grain aromas, and a leaner, more classically-styled mouthfeel with hints of baking spice from the barrel aging. It's not a full throttle high proof experience, nor is it a softer, gentler spirit like the Bulleit or Templeton products. It falls somewhere in between Russell's Reserve 6 and Rittenhouse, if you're looking for a comparison, but after multiple tastings it's clear that the Corbin is its own thing—a purely Californian whiskey, 100% from farm to bottle.

I have a feeling 2014 will be an important year in the annuls of small-production whiskey (I'm disowning the word "craft" from this point on because I think it adds a negative connotation), simply because it's the first year where smaller distilleries have begun offering viable alternatives to the big-boys at reasonable prices. Both Willett and Corbin have turned in fantastic rye whiskies this month, and there are a few more regional secrets I'm sitting on for later this Fall. More importantly, we're back to working with families rather than global conglomerates, which is much more fun for me. There's something wonderful about two family-run, California businesses bringing booze to the people—K&L and Corbin working as farmer and merchant.

That's as romantic of a story as I can tell in the booze business—and the whiskey tastes good, too!

-David Driscoll