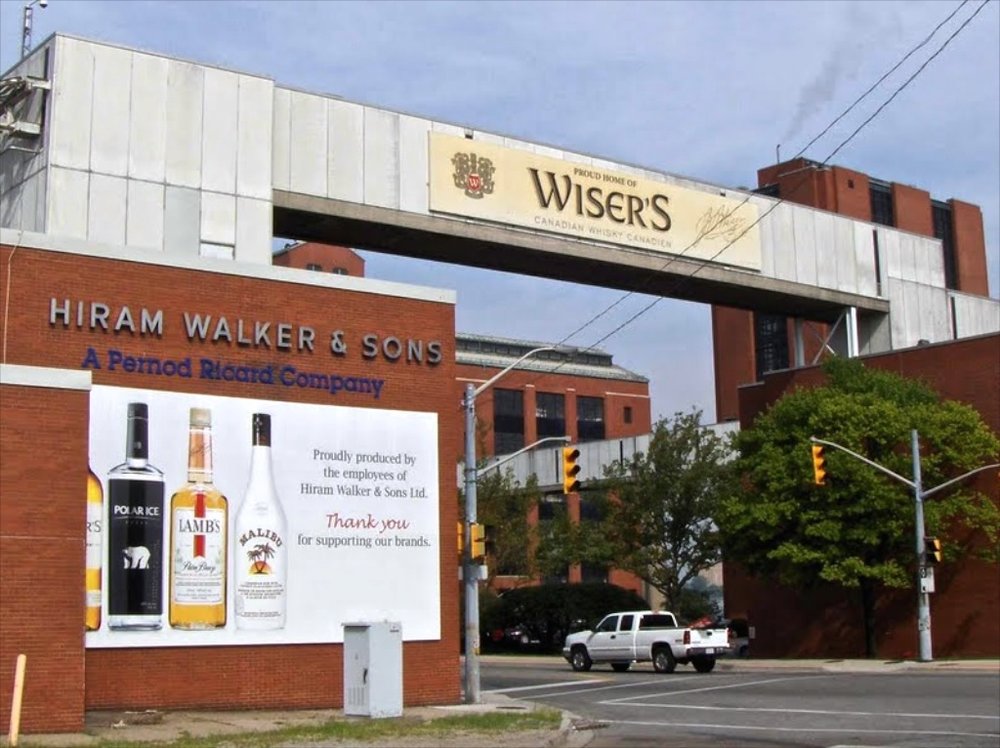

More on Canadian Whisky: Hiram Walker

As I was saying last week, I got the chance to visit with Hiram Walker master blender Don Livermore recently and was thoroughly impressed by his knowledge. You ask the guy one question and he gives you ten questions worth of answers. He's fantastic! I'm of the firm belief that Canadian whisky is going to do some big business in the United States this year. There's too much good stock north of the border and the prices are simply too affordable to pass up. That being said, there's too much I don't know about Canadian whisky to make educated and confident decisions about what direction K&L should take as a company. How is Canadian whisky made? What makes it different from other rye whiskies? Why does it taste the way it does? And why do Canadians like their whisky that way? These are the main questions I needed detailed answers to.

That's why I decided to phone Don Livermore and recreate the conversation we had in the Redwood City store for everyone's benefit. He was hanging out in his office at the Hiram Walker distillery in Windsor, Ontario—just across the river from Detroit—and was happy to take the call. Don is a super nice guy and he's very eager to help. I'm sure he'll continue to be a great source of information for us as we make our foray into the Canadian whisky category. As I'm planning on making a large purchase of Wiser's 18 in the near future, I wanted to make sure I had all my ducks in a row concerning its make-up—my i's dotted, and my t's crossed. Therefore, that's where we begin our chat.

Check out our conversation below:

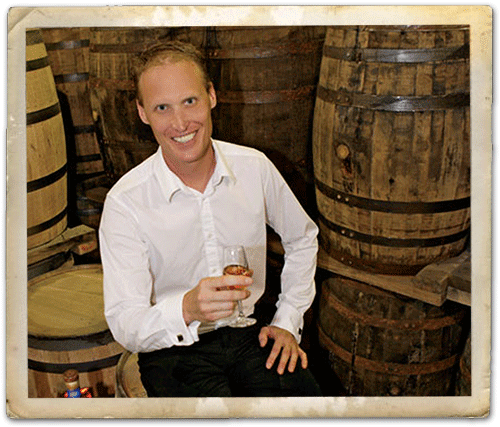

Hiram Walker distiller & blender Don LivermoreDavid: Can you tell me a bit about what goes into the JP Wiser’s 18? I know there are going to be a lot of people interested in an 18 year old Canadian whisky, but they’re going to want to understand more about it.

Hiram Walker distiller & blender Don LivermoreDavid: Can you tell me a bit about what goes into the JP Wiser’s 18? I know there are going to be a lot of people interested in an 18 year old Canadian whisky, but they’re going to want to understand more about it.

Don: With Canadian whisky we ferment corn, rye, wheat, and barley separately, distill them separately, age them separately, and then blend them together at the end. That is why they have a job like mine as a master blender. The distilling of Canadian whisky can be done by a number of different techniques. There are three types of distillates that we make at the JP Wiser’s distillery. One pass through a copper column still produces a full and robust spirit from all the grain characters and yeast congeners. This is similar to that of a Bourbon distillation. A second pass through a column still removes most of the characters to make a lighter-smoother base whisky, traditional to the early Canadian whisky styles. We can also use pot distillations to create concentrated distillates that add unique characters and complex aromas to our brands. So in Canada we can use either a single column distilled spirit, double column distilled spirit, or a combination of column then pot distilled spirits. JP Wiser’s 18 year is a blend. The majority of the blend is a double column distilled corn whisky which makes a smooth tasting spirit. There is an added amount of single column distilled rye whisky which gives a subtle peppery nuance or a spice to the blend. All the whiskies are aged entirely in used Canadian whisky barrels. I’ll often describe the brand as: the taste of the angel’s share.

David: What about the taste of rye? How important is that particular grain to the flavor?

Don: One thing that drives me crazy is when people ask me the percentages of the grains we use, either for mashbills or distillates because via the distillation process we can concentrate up the character of rye or we can strip out the character of rye. The more pertinent question is how is your whisky distilled? If the product is double column distilled it strips out the character of rye, if the product is column distilled then pot distilled then it concentrates up the character of rye. I like to say: we’re brewers as well as distillers.

David: Can you expand on that a bit?

Don: Sure, we all distill differently and we pull out things at different boiling points. The tradition of Canadian whisky, if you go back into the history books, begins with a patent made by a company called Gooderham & Worts that started double-distilling their whisky through two column stills to make a lighter smoother whisky in order to compete with moonshiners. The consumer didn’t want the moonshine taste, so the double-distillation made a lighter, smoother style. In 1830, there were about 230 registered distillers, and by the time we get to about 1870 there were only about fifteen left; and those were the guys making that lighter-style spirit. That’s why Canadian whiskies tend to be light and smooth. While they primarily used corn, they would also utilize the properties they had around their distilleries, which grew rye. So they would make their rye whiskies; either single column distilled, or column distilled and pot distilled—which concentrates the character of the rye.

David: The JP Wiser’s 18 year is made primarily from the smoother base whisky, right?

Don: The 18 year is largely that double-distilled spirit, traditional to Canadian whisky. In aging our whisky there are four things that happen in a barrel; one of them is a chemical reaction. Oxygen going into a cask will first displace the whisky, taking the angel’s share, but when oxygen hits ethanol it turns it into something called ethyl acetate. Ethyl acetate smells and tastes like a green apple. It gives you that tingly note on the palate. When you age something in a barrel you expose it to oxygen, and for us we create about ten parts per million of ethyl acetate per year. If you can remember your science days from high school, chemical reactions are induced by heat. Here in southern Ontario, I’ve never seen a place that ages whisky that gets as extreme of a temperature change as we do. The warehouses have no electricity because they’ll go “Boom!” if there’s a spark, so that change of temperature expands and contracts the barrels—the oxygen going in and out—during the warms days and cold nights. When the warm air comes in and interacts with the cold whisky, we get condensation on the outside of the barrels which ends up rusting the hoops. When the Scotch guys come to visit our warehouse, they ask: “Why are all the hoops rusted on the outside of your barrels?” It’s the drastic change in temperature, which you don’t see in Scotland.

David: So the flavors in the JP Wiser’s 18 come from that reaction?

Don: That’s the taste of the angel’s share, the oxygen interacting with the whisky, the ethyl acetate, that tingly, green apple character, which ultimately becomes the dominate character of the whisky.

David: I like that you keep using the word “tingly” because when I wrote the tasting notes for our website that’s exactly the word I used, and it’s not a word I use often. It makes me feel better now about my description.

Don: Remember this tingly character because you’ll find it in Scotch, but it often gets buried under the peat or the sherry. You’ll find it in Bourbon, but it’s often buried under the grain and the yeast characters because they only column distill it once.

David: That’s interesting because some discerning folks consider the double-distillation to be a drawback rather than an attribute. In this case, it’s actually part of the tingly character.

Don: With the double-distillation you create the lighter smoother style, and that’s right there in your face. After 18 years in wood, you really get the taste of age in the JP Wiser’s 18. That’s what highly-aged whisky should taste like, in my opinion.

David: I think there are a number of whisky drinkers out there who would like to understand how the JP Wiser’s 18 differs from another of your famous whisky—the Lot 40.

Don: Right, the Lot 40 is 100% the polar opposite. It’s 100% rye whisky. The rye is passed once through a column still and then a pot still. When yeast ferments, it makes fruity, floral, green grass, soapy, and sulfur characters. We can control the fermentation’s temperature, the nitrogen level, the pH, grain levels or a number of other things in order to influence the yeast to make these characteristics. We do a warm ferment that helps the yeast grow quickly and ultimately make alcohol quickly. After 3 days of fermentation we achieve 8% abv. When you put that fermented rye mash once through the column still you keep the grain character (spicy), as well as the floral, the fruity, the green grass, and the soapy notes that yeast has made. What’s missing? The sulfur. Where does it go? It actually salts out in the copper column still to create copper sulfide. So at the end of the week we actually have to clean out our stills to remove the salt residue. We then pass the column distilled liquid through a pot still for Lot 40.

David: The JP Wiser’s would not fall into that category.

Don: Right, with the JP Wiser’s we strip out the grain character. I could make that whisky from corn, rye, wheat, or barley and you wouldn’t know the difference. A brand could call itself 100% rye, but the question, of course, is: how was it distilled? If they say it’s double-distilled through two column stills, then what’s the point of calling it rye? The rye character has been stripped out. Remember we’re brewers as well as distillers. When you’re distilling, you separate those compounds out at different boiling points. Or, you can concentrate them, which would apply to the Lot 40. You column distill it, take that liquid, and put it into a pot still. You know about heads and tails from there; the low boilers come out first, those are your green grass notes. We cut that and take it out of the whisky. What comes over next are the fruity characters, then the floral characters, and as the pot gets hotter, next come the grain characters. What’s left at the end are the soapy characteristics from the yeast, from the fatty acids in the cell wall. Those are your tails.

David: And that intensifies the rye flavor?

Don: Yes, you’ve taken out the green grass and the soapy part, and you’re left with the fruity, the floral, and the rye notes. The more pertinent question is, however: how much 4-ethylguaiacol is in the whisky? Rather than ask how much rye is in the mashbill, this is what people should really be asking. That is one of the phenolic compounds that actually bring out the rye spices. This is what I mean when I say we’re both brewers and distillers, separating the compounds at different boiling points.

David: Can you explain that a bit more?

Don: Sure, so when you’re pot distilling, you’re raising the temperature of the liquid. As you get to 21oC acetaldehyde will turn into a vapor, come over into the condenser, and that becomes your heads. Dimethyl sulfide boils at 37oC, acetal at 55oC, so we’re cutting out those components. Once we hit around 77oC, that’s where the ethyl acetate comes out—that nice fruity character—and that’s where we start doing the heart cut.

David: So when you’re distilling any grain, you’re really looking for the boiling points of those characters that yeast makes, which you will then use to dictate the flavor of the spirit.

Don: You got it. So at 235oC, you’ve got the 4-ethylguaiacol, which is right near our tails cut. The soapy characters are around 260oC. Pot distilling is basically like boiling soup—it’s not that difficult. I will also say that the temperatures can vary from still to still as the pressure of the still will also influence the boiling point of each compound, but you get the idea that yeast or grain characters are separated on boiling points.

David: So what do you say to folks who are uninterested in Canadian whisky—things like JP Wiser’s 18—because they feel the grains are unimportant to the flavor?

Don: With Canadian whisky it’s more about the taste of pure age than the taste of the grain. It’s the angel’s share flavor, the reaction of the ethyl acetate, and that green apple, tingly flavor we talked about. Obviously, you’re going to get vanilla, caramel, and toffee, along with that little bit of peppery rye that we blend in. That’s the Canadian whisky style. This is what aging does, and in my mind it doesn’t get any better than that. With the climactic changes we get here in Windsor, it really drives home that flavor. I always tell people: taste the JP Wiser’s if you want to know what good, aged whiskey tastes like. There’s nothing else getting in the way of that flavor.

David: Basically, it’s the pure taste of concentration through evaporation?

Don: Yes, along with reaction—that oxidative reaction we talked about—so concentration along with reaction.

David: The JP Wiser’s portoflio is entirely made from blended whiskies, right? It’s not just one in any of the expressions?

Don: Right, the JP Wiser’s has the double-distilled column still whisky and the single column rye. We don’t use the pot distilled whisky in it. We want the dominate character to be the age, not the rye. Not everyone likes the peppery flavor of rye, so we like to give people options.

David: When you’re double-distilling to ninety-four percent, do you think that detracts from the quality of the spirit you’re making?

Don: The spirit we’re making is heavier than the heaviest vodka, so it’s not lacking in character. We want it to be light and fruity and smooth. Plus, we’re eventually blending in some of the rye spirit. We’re still working with flavor compounds here.

-David Driscoll