D2D Interview: Chaz

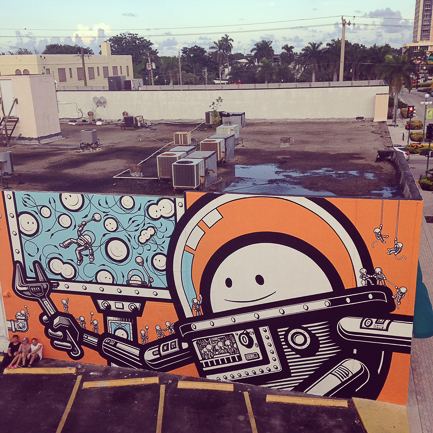

I know I said I was done doing the Drinking to Drink interviews for a while, but if there's one thing I've learned over the past few years it's that you can't predict the future. You can make an assessment or try to lay down a few ground rules, but ultimately you have to just go with the flow. The more I talk to interesting people around the world who like to drink, the more I get introduced to other interesting people of the same nature. Take Chaz here, for instance. Through the magical world of e-communication I came into contact with one of the most popular street artists on the planet, a man whose job it now is to fly around the world, create beautiful imagery, and have a few drinks along the way. I said to him, "Hey, you and I have something in common, minus the whole create beautiful imagery part." The London Police is an art group started by Chaz and his mate Bob back in 1998 that started out doing graffiti art on the street. Today, the two English sensations get paid to create designs and murals by fans of their work all over the globe.

As it turns out, Chaz is a big fan of both wine and tequila, so we had plenty to talk about. Being someone who's genuinely curious about artistic subcultures and underground movements, I had plenty of questions. What I love about Chaz's work (and street art in general) is that it often seeks to visually improve forlorn or forsaken parts of the urban landscape with an interesting and stimulating image. The fact that those images are often illegally-drawn or unasked for only makes the work that much more compelling. But we'll get into all that, don't worry! In this edition of Drinking to Drink we talk about the origins of street art, why tagging is one of the last true forms of democracy, and how having a few friends around usually makes drinking that much more enjoyable.

Previous editions of the D2D series can be found by clicking here, or by visiting the archive in the right hand margin of the blog.

David: How does one even get started as a popular street artist or as a tagger? Obviously you can just go out and do it, but what else beyond that? What makes one a professional?

Chaz: I would say ambition, desire, hard work, luck, and an honest direction. I would equate it to a young band trying to make it. On one hand they look to the future and think about getting a deal, selling records, and making money, but half of them do it just because they love making music. They say, “Let’s see what happens. Let’s just do it.”

David: Where did you fit into that?

Chaz: I started an art crew with a couple of friends and I was very much engaged in the hip-hop/graffiti thing that came over to Europe in the eighties, but I never really managed to nail down being a graffiti artist. That’s when I got into music with my own band and selling T-shirts for other bands, as well as working for music venues here in Amsterdam when I moved here. By the age of twenty-four, Bob and I were photographers and our idea was to take photos, paste them up on the wall, and try to twin different media of the art world with street art. This was just before street art was really coming through, and I had these characters I was drawing at the time—just doodles, really. I started drawing them on the streets of Amsterdam, and Bob joined me, and within six months to a year everyone was talking about these characters.

David: People began recognizing them from their daily lives around the city?

Chaz: Yeah, we’d gone from having this idea of wanting to be an art crew to being quite infamous, really. It gave us a little platform to work from which helped with our other artwork. Sooner or later, shops or brands would ask us to show work or do designs for them. We started traveling around the world at that point, hitting the streets in different cities and doing the same thing. Right at this time the internet really boomed and the street art scene took off because you had certain websites that would highlight people around the world doing this—tagging, putting up posters, more fine art styles as opposed to graffiti or hip-hop art.

David: What are the main differences?

Chaz: There’s a fine line between what we do and what other artists on the street do, but like anything you can categorize it. There’s political graffiti, vandalism graffiti, train graffiti, tagging, throw-ups—the list is endless. We found ourselves in that part of the scene and then just continued to get more successful.

David: Do you like to drink while you work?

Chaz: In the early days I was pretty brutal. The other guy in the London Police is a guy called Bob. Bob is much more family-oriented, he’s got his kids, he likes his fitness and his cycling. He doesn’t like to party as much. He’s been known to, but I was very much the partier—smoking a bit, having a few drinks, meeting people. But as I got older I started to change and I didn’t want to turn into a massive alcoholic. What I really wanted to do was have less quantity and more quality.

David: What did you start drinking once you gravitated to that mindset?

Chaz: As a teenager in England you start with cider. At the age of fourteen beer still tastes quite bitter, so the sweetness of the cider makes it easier. We used to get hammered on cider and then eventually it became beer and pints. One of the biggest wine influences for me was an artist friend called Galo, he’s from Torino, Italy and he has a family house in Piedmont about half an hour from Barbaresco. I met him in Amsterdam in the early days as an artist and he introduced me to wine. I was an English guy, buying the cheapest shit possible, and he introduced me to Barbaresco, which he loved because he had done his military service there up on the hill. He said every day he would drink different vintages. I was still very much going out on the piss, necking a bunch of pints, I didn’t know about the quality of wine.

David: Do you still drink wine on your own?

Chaz: I drink everything. I could never give up wine, but I could give up beer if I had to. There are times when I enjoy beer and I like the fact that it isn’t so strong. You can get some very nice Belgian and German ones out here which are more sit-down-and-enjoy-it-slowly type of beers. As for wine, however, it’s my first choice. I love it with food. I love learning about it.

David: How does it fit into your creative moods? Do you find that it adds to your process?

Chaz: I definitely use alcohol in my work. I’ll be forty-two this year, so I’m aware that I can’t just drink like I used to. I’m trying to drink the best stuff that I can. Tequila is my drink that I take to the studio, however. If I’ve got a session where I’ve got to paint a load of stuff and I need to let go and be creative, it would be tequila and pot, really. Red wine I reserve more for special occasions and dinner time.

David: That’s interesting to hear. Why tequila?

Chaz: Well, I hear people say that tequila is one of the few liquors that’s actually more of a stimulant than a downer. That’s what I’ve heard. I don’t drink it for those reasons, but that might explain why I physically enjoy the drink.

David: Is there a big selection in Amsterdam?

Chaz: The tequila you get over here in Europe isn’t of high standard, therefore no one really drinks it. If they do have nicer bottles then they’re expensive, but since no one over here really knows anything about tequila they can’t justify spending more. As you and I know, there’s generally a reason why alcohol is more expensive: because the quality is better. I’ve had a lot of rotten hangovers in my life, but I’ve never had a bad night drinking tequila. I’ve only had great nights. If I stick to tequila and don’t mix too much, I’m usually alright. Wouldn’t you agree?

David: Absolutely. I know a lot of people who love tequila for that reason. It gets you in the party mood, you don’t get too drunk usually, and you feel better the next day. It’s true for me as well.

Chaz: It’s a powerful drink; it really is. It’s interesting to see how it goes up in quality levels, too. I have a friend in Fresno who runs a Mexican restaurant and when he came out to a friend’s wedding, he brought out a Patron aged in wine barrels. It was wonderful. I love the high-end Tapatio, too. Everything I’ve had that cost over a hundred dollars has been excellent.

David: How would you explain your line of work to someone who doesn’t understand street art?

Chaz: I would just say I’m an artist, like a musician would say he’s a musician. Are you an opera singer or a concert pianist? I make my living selling paintings. We do mural artwork quite a lot where a hotel will bring us in to paint the lobby. Right now we’re painting the lift shaft in a millionaire’s house over in Brussels. In two weeks time we’ll go to Dubai where we’ll be painting the side of a wall for some famous sheik. The list goes on. I’ve been doing this for eighteen years and you take each job on its merit. But to touch on your question, some people say street art started when Martin Luther King was assassinated and a lot of the black kids went into the city streets to write political messages about it. Others suggest it started by messengers in New York back in the 1970s, and the first guy was called TAKI 183. He was a messenger kid who was up and down Manhattan a bunch, and he signed it 183 because he was from 183rd street. So that took off and of course the kids loved seeing their names on the train, it gave them a sense of self worth and pride. Then the whole hip-hop thing happened and it just took off from there.

David: There’s a clear history and timeline there. That’s fascinating!

Chaz: There has always been graffiti, in fact the name comes from the Italian graffito and they talk about the days of Rome where groups would be underneath the arches writing political messages. Look at cave painting, too. The first time man wrote on a wall was almost like the first glimmer of art. It’s the leaving of something so that someone else can read it. In some ways it’s one of the last true forms of democracy. I can go out tomorrow and write something on a wall and you have to read it! You actually have to read it to know you don’t want to read it. There’s a sense of ego with it, too, when it comes to tagging. It’s as charming as it is vandalistic in a sense. If someone wants to write their name out so they can see it the next day, you can take each case on its merit. You have to think: was it in the wrong place, did it upset someone, did he have the right to do it? If I write on the side of a derelict house, perhaps you don’t care so much. But if I do it on the side of a church that’s different, isn’t it?

David: There’s a certain communal aspect to it, which I enjoy actually. You’re talking about selling art to private customers or doing work inside their homes or hotels, but if you do something on the street it’s there for everyone—anyone can go and look at it.

Chaz: That’s right. It’s a certain form of entertainment. You never know where our artwork will turn up, but at a certain point when you paint on the street you do start to see the fruits of your labor go unnoticed. Maybe it gets crossed out, maybe it gets covered up, or maybe someone steals it. Then you think: “I just spent an hour doing that. Maybe I can do it on a canvas instead.” That’s how you make a career out of it. But there is a certain thrill about going out on the street and doing something with an illegal edge. We used to call ourselves the A-Team of the art world. When you watched Hannibal and BA pepper guys with bullets and smash the hell out of them, you’d say: “That’s all right, they’re the good guys!” No one ever really died, right? If you can go out and do something illegally, but get away with it to where people look at your work the next day and say: “Well that looks better. That wall was just fucking horrible before. Now it looks great!”—then there’s something to that. That’s why people are so obsessed with guys like Shepard Fairey in your country. They wonder if it’s art or vandalism and that brings the subject to the forefront of people’s attention.

David: It’s almost like moonshining in a way, if you had to find an alcoholic comparison. You’re making booze illegally without a license, but if it’s good people will want it and maybe that leads to an eventual legitimacy down the line.

Chaz: Absolutely. That’s a perfect example I think.

David: Do you ever drink while you’re out painting a mural?

Chaz: In the early days it was only about drinking (laughs). We’d say, “Hey, I forgot the bottle. Let’s go back and get it.” It was more important than the pen! They did go hand-in-hand. To be honest, when you’re out there and it becomes more of a mission—where we’re actually using walkie-talkies to communicate—it helps to have a little bit of courage. It helps take the edge of fear away. I quite often take bottles of tequila everywhere because I know that once I’ve shared a few shots people will loosen up. They’ll actually look at you for an extra few seconds—they’ll lock eyes with you—and they know that you know that they know they’re drinking some quality shit. They’ll put the glass back down and say, “Can I have another one of those?” And you’ll say, “Definitely! Because you recognize that this is the good stuff!” It’s one thing to drink good stuff on your own, but when you can share it with someone else that’s the key.

David: Having good people around always makes life better, in my opinion.

Chaz: It reminds me of that old joke about the guy who gets shipwrecked while on a celebrity cruise. He grabs a bit of wood in the midst of the storm, he manages to hang on, and the next morning he wakes up on the beach. He’s alive and he looks down the beach and he sees Claudia Schiffer laying down at the other end. It’s only them two on the island, and after a few days he says to her, “I don’t think we’re going to get rescued.” After a couple more days, he says, “Since we’re not going to get rescued maybe we should get used to the idea that we’re alone together,” and they start having a bunch of sex. So this guy is fucking Claudia Schiffer on the beach, the weather is perfect, there are palm trees everywhere, and he’s thinking: “This is unbelievable!” A couple of weeks go by, it’s all kicking off, and suddenly Claudia sees him at the end of the beach, sitting on a rock, looking pensively out at the sea. So she walks up to him and says: “What’s wrong? The guy tells her he’s sad. So she says, “You’re sad? You get to sleep with me every day, we’re here together in paradise, and it looks like we’re stuck here forever. What’s wrong with that?” He looks at her and says, “I know, but I haven’t got any mates here I can tell about it.”

-David Driscoll