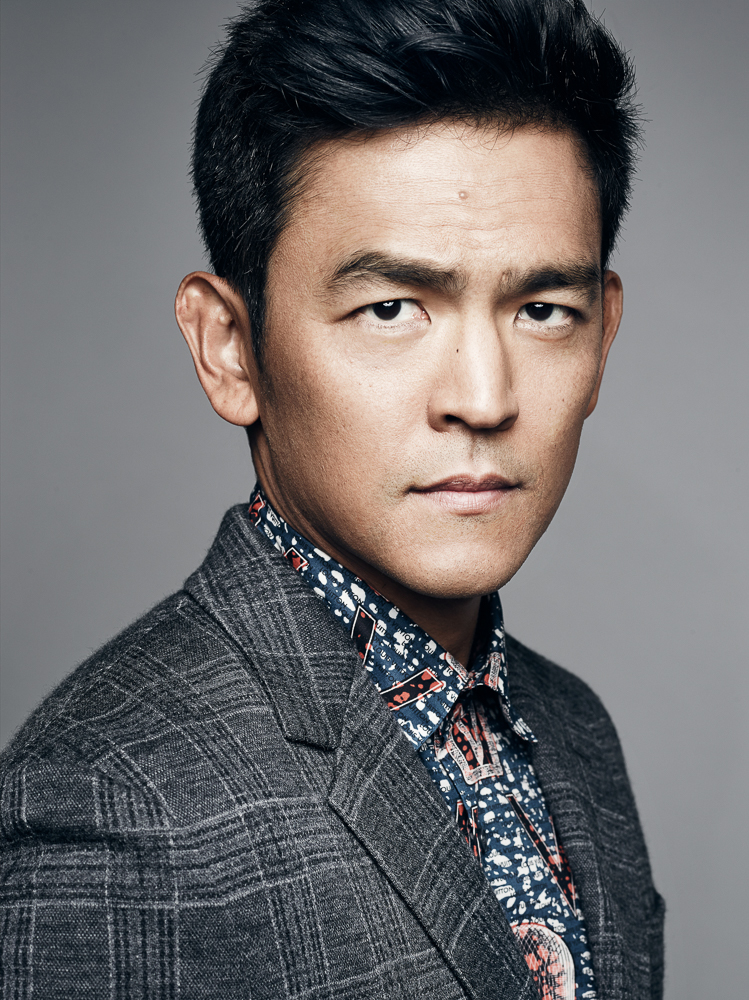

D2D Interview: John Cho

It was at a private party in Hollywood one night that I found myself unexpectedly drinking cocktails and talking booze with actor John Cho. We were both taking a break from the party's social center, sitting by ourselves at an outside table while trying to catch a bit of fresh air. I asked him what he was drinking. He asked me about my drink. The conversation started from there and it continued on and off for the rest of the evening, each new beverage leading to a different discussion about our personal preferences. I liked him immediately; he was unpretentious, down to earth, and it was clear he was interested in all things wine and spirits. Before leaving that night we exchanged numbers and I told him to give me a call if he ever needed help stocking his home bar. After sending a few bottles of rye whiskey his way, I thought it might be time to restart our initial conversation in a more professional capacity and after watching John's latest film Colombus this past holiday season, I knew the moment was right. If you only know John Cho from the Harold & Kumar films or as Lieutenant Sulu in the recent Star Trek revival, you'll be blown away by his recent dramatic performance in the beautifully-shot drama, set in an Indiana town noted for its modern architecture. It's a movie reminiscent of Lost in Translation or Sideways in both its mood and its storytelling, yet it's a more complete and moving picture than both of those films, in my opinion. Not only was I personally wowed by the aesthetics and atmosphere of Columbus, I found myself brimming with booze-related questions for John due to the film's dialogue concerning perceptions of personal taste. I couldn't wait to get him on the phone to talk about the comparative analytics.

We started with a brief discussion about the impact of California's recent legalization of marijuana and dove in further to drink-related topics soon after. Our conversation continues on below:

John: This is an interesting point of discussion, the kind of alteration that you prefer. I’ve always preferred booze the most. I like the relaxing aspects of weed, but I don’t like losing my acumen. I’m able to have a conversation when I’m drinking and that’s an important part of the fun for me.

David: My wife and I feel the same way. If we do the edibles, then we’re not going out because it’s tough to be social at that point. If we’re going out with friends, however, then we want to drink.

John: Right, the social aspect of booze is great. Conversely, it’s the anti-social part of weed that I don’t like. The laughs are good though. Then there’s the taste part of it, which is a whole other world to itself.

David: Let’s talk about taste for a minute. I’m so happy that we waited to do this interview until after I watched Columbus because there are so many aspects of the movie we can talk about that apply to the booze world. Like Sideways, which has impacted my industry immensely over the last fifteen years, Columbus is a story about people with a central medium as its main character. In Sideways it was wine, whereas in Columbus it’s architecture.

John: Yeah, architecture is the vessel for talking about each others’ lives. In Sideways, wine is the language for talking about everyone’s feelings. Every single bottle is like a little poem. I didn’t really know anything about architecture before taking the role in Columbus and I tended to evaluate buildings with my eyes. After the experience of making the film, I learned to evaluate them with my feelings—how a space made me feel and also what it made me think about. There are spaces that do that.

David: How did that change in appreciation come about? Was the writer on set to help guide you through?

John: Kogonada, the writer and director of the film, didn’t really push his opinions about the buildings upon us. We did do some research, but it was mostly being in the spaces and making discoveries as I went along. There’s a church there called the North Christian Church and it was very significant to me because I had grown up in churches all my life. My father was a preacher and being in that church I could see how we were meant to think about God in the way the space arranged. If you think about a cathedral in Europe, like Notre Dame in Paris, there are gargoyles all over the place and you’re meant to fear God, to know that he is much bigger than you. The way the pews are, you are below the speaker. The speaker is between God and you—above you, but below God. There’s all this information that you get based on the spacial arrangement.

David: Did that differ from your experiences as a child growing up in church?

John: When I was growing up I went to the Church of Christ and these buildings were all unadorned. They were purposefully built that way because it was a reaction against the Catholic Church and they wanted the buildings to manifest that. Being at the North Christian Church in Columbus, the seating was in the round. The speaker was sunken below the congregation. It was a very holy place, just as holy as the Vatican, but the speaker was a servant below the congregants, and when you looked out into the church you were actually looking at one another because of how the seating was in the round. I found it to be a space that made me think about community in a different way and about God in a different way. I think that’s what I understood after making the film: how does a space make you feel and what does it make you think about?

David: There’s a very profound moment in Columbus where your character is getting a tour of a famous building by Haley Lu Richardson and she says it’s her favorite. You ask her why and she starts spouting off the history and the design specifics, but you interrupt her to say: but why do you like it? It was an attempt to cut through all the technical specs and mumbo jumbo, and get into the meaning of personal experience. For me, that line sent a jolt down my spine because it reminded me so much of my work in an industry where people use similar descriptions to describe why they like alcohol. It’s often more about proving what you know rather than voicing a personal opinion.

John: To me, that moment is the beginning of their journey together. The rest of the movie tackles the question of what architecture means to them, but the first question is: why do you like it? I felt like the whole film was an attempt to take something intellectual and make it personal. Particularly with architecture, and I can see why it would be the same for alcohol, the first impulse is to intellectualize the pursuit. It’s almost a guarantee to never enjoying it though, you know what I mean? It reminds me of my problem with acting. I fell into acting in college and I was good for those first couple of plays because I had no idea what I was doing; I was just a kid. It was just play to me. Kids are very good at playing, but then we become adults and we become very bad at playing. The work of an actor—and I don’t mean this to sound pretentious—is to go backward and become a kid again. It’s actually hard to do. When I decided to pursue acting and become a professional, that’s when I became bad at it because I took it so seriously.

David: You began to study it.

John: Yeah, I checked out books from the library and took a class and tried to approach it like I’d approached anything else up to that point in my life. I had only ever been a student, so I tried to approach it intellectually. Then I started working as an actor and it became a job. It took me years and years to really learn how to act, to go backwards and learn why this character was interesting to me or why a scene was fun to do. I had to find inspiration when I said yes to a part so that I didn’t come into it thinking of it as a job, but rather as a fun opportunity to do something new. Looking for specks of joy in any project is what I now do, but it took me a long time to figure that out.

David: Was there a moment when you realized you were doing it wrong?

John: I think there was a moment when I got cast in the first Star Trek. What I remember was experiencing a joy that was connected to my childhood and my sense of play. It was fun pretending to be on a spaceship and putting that gear on. It was exactly what I did when I was ten years old, which was pretend to be on a spaceship with my little brother. I thought to myself: I need to look for this in every role, some semblance of this joy. I remember feeling a little depressed before that and that was the role that made me think: acting is fun again. Even in a comedy like Harold and Kumar, which seems like it should be a blast, I wasn’t having as much fun as I should have been having because I was so concerned about doing it right. When you can let go of that fixation, you can get to a bunch of other places.

David: It’s amazing to hear you say that because I’ve felt that same way so many times. I’m doing this great job tasting booze all day that should be an absolute blast, but I often struggle with those exact emotions. It’s actually the reason I started doing these interviews. I thought to myself: I need to find something that I really enjoy doing in order to make this fun again, and that’s why we’re talking now. I think you have to constantly search for that inspiration, otherwise you go over the edge.

John: I hesitate to call it this, but I think it was a bit of an existential career crisis. My job doesn’t allow me to move around from town to town, or live wherever I want to. I suppose I could have quit acting altogether, but with whatever job I would have landed afterward—like if I was the night manager at Kinko’s—people probably would have come in and said: “Hey, you’re the guy from that movie! What are you doing here?” It would have been a constant reminder of my failure as an actor and I felt sort of trapped. It’s kind of a one-town industry, so I was committed, yet I was having a hard time having fun. It’s a constant internal navigation to try and find different points of joy.

David: Is drinking something that brings you joy right now?

John: Yeah, sometimes I feel like I rely on it too much, to be perfectly honest. But then my curiosity about different kinds of spirits tempers that because then it becomes less like medicine and more like fun. I think you don’t want to depend on alcohol to do something to you, but rather to be open to it doing something different. That’s where the fun part comes into it. For me, discovering different things is what I want to do, rather than simply wanting alcohol to do something to me. That sounded depressing, didn’t it?

David: Ha! No, actually it makes total sense. What did you think of that last bottle of rye I gave you? Was that fun to experience?

John: I loved it. I don’t know that I have the whiskey vocabulary to describe it, however.

David: Let’s go back to your architecture analogy then; how did it make you feel?

John: It made me feel light, in a good way. Buoyant. A smoky Scotch will make me feel solid, very grounded, here in one place, but rye for some reason makes me feel lighter, like I’m floating, and I don’t know exactly why, but I like it.

David: Did you know anything about that whiskey before I gave it to you, or were you just thinking: “I’m trusting Dave that this is good stuff.”

John: No, I was just trusting Dave! By the way, I’m actually in a place where I prefer not to know anything about the bottle beforehand. I’ll tell you why. Years ago, a friend of ours gave my wife a bottle of wine for her birthday and we just put it in the pantry; we didn’t have any sort of wine fridge at the time. Then we forgot about it and a couple of months later an old friend dropped by and we started to cook for him. My wife went into the kitchen and asked if we had any wine. I said: just the one bottle, and she said: open it up. I remember looking at the label and thinking it looked fancy, so then I Googled it and it was like a $1400 bottle of wine. Then I was panicked! I said, "What have we done?!" We’re supposed to open a bottle like this when we beat cancer or are elected president. You can’t just open this on a Sunday afternoon, can you? It was really interesting to watch my wife and our friend react because after the initial shock they were still able to enjoy it. I drank it and it tasted great, but I don’t know whether I really enjoyed it because I was thinking too much about the cost.

David: That happens all the time. There are definitely times when thinking or knowing too much about alcohol prohibits our enjoyment rather than enhances it.

John: Right, but sometimes historical information or a fun story helps.

David: Agreed, if there’s a story, or a legend, or a piece of historical background that makes you feel special for drinking it, then that’s great. But sometimes learning too much about the technical details gets in the way. For example, I know multiple customers who have been unable to drink some of their collectable whiskies given what they're worth in today’s market. Let me ask you this: if I told you that Handy rye whiskey I gave you is considered by many to be the best in the world and that there are grown men out there who would sacrifice their oldest son to get a bottle today, how would you feel about it now? Is it still something you're going to enjoy?

John: Now I’m all tight (laughs). I don’t think I can enjoy it anymore. I shouldn’t have had any last night! Oh God!

David: Does knowing that change the way you’re going to approach it now?

John: Now I’m going to want to drink it with people that I like. I don’t want to drink it alone anymore. That much goodness should be shared. It should be a social experience. Going back to the weed versus alcohol thing, having that shared social sensation is a particular sort of kinship even if you’re ordering different drinks from a bar. But if you’re sharing the same bottle, that’s an even greater intimacy that I like.

David: Shared experiences are ultimately what bond us as humans and open us up to transformative social experiences, in my opinion. That’s where I have trouble with the internet today. I’m losing the ability to relate to new friends and colleagues because we don’t have those shared experiences in common. We no longer watch the same shows, nor are we forced to watch the same dumb commercials. It’s a bit of a tragedy, in my mind, because I interact with customers who are looking for someone else they can talk to about their whiskey and wine experiences, but can’t find anyone near them to share their booze with. However, if you can create a new shared experience together, over a bottle like you pointed out, it’s a way of getting that intimacy back.

John: Yeah, I will say there is a certain mono-culturalism that the internet is encouraging. Yet, in other ways it is fragmenting us. Meeting people over the internet is a completely different experience than meeting them while drinking face-to-face.

David: I don’t think we’d be doing this interview right now if we hadn’t originally met face-to-face while drinking, do you? If I had tried to reach out to you over the internet via some cold call email, do you think you would have said yes? Our shared drinking experience gave you at least a certain amount of comfort beforehand that this might be worth doing.

John: Absolutely, you’re totally right. I am one of those people who is suspicious of people who don’t drink (laughs), even though I come from teetotalers.

-David Driscoll