Blending Exercise

There's a great book about single malt whisky called The Whisky Distilleries of the United Kingdom published in 1887 by a man named Alfred Barnard. I turn to this book every now and again when I'm looking for information or inspiration about my drinking habits. The tome is a giant travelogue that documents Barnard's visits to active distilleries in England, Scotland, and Ireland towards the end of the 19th century and there are even blending tips and advertisements in today's reprinted editions. One chapter I had never paid much attention to was the section called "The Art of Blending Scotch Whisky." I probably wouldn't have ever paid it much attention had John Glaser not pointed it out as a source of inspiration when we visited him recently.

Having read through the section today, during the commercials between Mad Men, I managed to pull out a few interesting passages that I thought I would share with you here on the blog.

It is a fact well known that the old-established Scotch houses, above all others, are enabled to give a higher class of whisky, by reason of their careful study of the science of blending, which they have now reduced to a fine art....The idea is, to produce a blend so perfect that it strikes the consumer as being one liquid, not many – i.e., having absolute unity, tasting as one whole.

To anyone who's recently found an affinity for single malt whisky (me included), it's important to remember that the idea of drinking the whisky of one single distillery is a relatively modern phenomenon – as in within the last few decades. It's not that single malts didn't exist before then (Laphroaig was one of the first to pioneer the idea back in the early 1900s) it's just that blends were considered superior. Barnard's view is among the majority of opinion during his time. Creating truly top-level whisky required a knowledge of blending.

It should be remembered that a high-class blend cannot be made out of inferior whiskies, and that the first brands of Highland whisky are not procurable at a low price, or at least the same price as second and third-class brands, while experience will teach that it will be cheaper in the long run to use only the finest product of the finest pot stills.

As you can see from the above passage, there was no prevailing mindset among Barnard's group that the finest whiskies should be enjoyed on their own – unadulterated, from a single barrel, at cask strength. In his mind, the finest whiskies should be married together to create the highest-quality of blends – the highest echelon of whisky available.

Age is the first essential in Scotch whisky: common experience has always shown that new spirit is less wholesome and more intoxicating than old....For an ideal blend the age should range from seven to ten years, and for a high-class whisky for ordinary private trade the age should run from five to seven years, while for a public-house trade it should never be less than two and up to four years old.

Isn't that funny? Seven to ten years old for the ideal blend! My how times have changed. What's interesting is how surpluses and shortages affect the "ideal" age for Scotch whisky. I'm not going to deny that thirty year old Port Ellen tastes like pure heaven, but there is a good deal to be said for marketing. There was a glut of Scotch whisky in the early 1980s. Since that time we've been told that the older a whisky is, the better. Maybe that's because companies were sitting on vast supplies of old booze (Stewart Laing told us how they once blended old Brora into their basic label expression because they didn't know what else to do with it). Now we're in the middle of a global shortage. All of a sudden we're being told that age isn't important. In fact, many whiskies no longer carry an age statement. We're back to flavor again. The ultimate marriage is more important than the age of maturity. It could be said that the importance of age to a whisky depends entirely on what the industry needs to sell. I'm not saying that. I'm just saying that you could say that. :)

Speaking of flavor...

Flavour is the next essential in a good blend. All Highland whisky must have flavor, and it is the quality and degree of this flavour that denotes the value of the various Highland stills, just as it is in wine....A first-class blend must contain a careful selection of the choicest products of the Highland stills mellowed by age, and judiciously amalgamated by a practised hand; not like a mixture we heard of lately in the Midland Counties, in which a merchant had put together a second-rate Campbeltown, a cheap Lowland malt, and a deal of low-class grain spirit, and then called it a Highland malt.

How awesome is that paragraph?! Barnard is the outspoken whisky blogger before there was such a thing. Look at him, exposing companies that attempt to market their whisky as something it isn't. Fuck that shit!

Mountain air, peat moss of the richest quality, pure water from the hills, and the best Scotch malt, are absolute requirements for the manufacture of Highland whisky, in order to ensure the pronounced characteristics so highly valued by the experienced blender; and it is the development of these by age, which gives bouquet and relish to a fine blend. In order to appreciate good whisky we must fully realise the distinction that exists in the composition and properties of the blend....For the purposes of our argument we shall divide the distilleries of Scotland into six classes: Islay, Glenlivet, North Country, Campbeltown, Lowland Malt, and Grain.

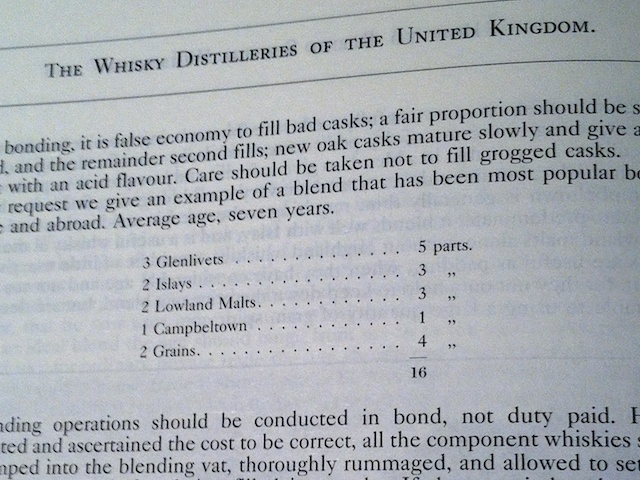

Glenlivet is what we know today as Speyside (confusion between the actual distillery and the region). North Country we now refer to as Highland. Barnard goes on to describe the properties of each style and its particular use for blending together the perfect whisky. He even gives a recipe for one of the most popular blends he knows of, which you can see in the photo at the top.

Looking at Barnard's recipe for inspiration I took to my whisky cabinet and began mixing. Are you like me? Do you have fifty open bottles that have been quietly sitting there in your living room, taking up space and needing an excuse to finally empty their content? Maybe it's time we all tried our hand at blending. I want to see who can make the best vatted malt from their home collection. I know a few customers who already do this regularly, but I think learning how flavors work together is part of a sound whisky education.

While the term "blend" today has become synonymous with lower quality with newer whisky drinkers looking for "pure" authenticity, mixing up what's available is a great way to find value in an exploitative market. We're doing some mixing of our own right now with casks that have potential, but don't quite sing that solo the way we wish they could. Barnard's book is a great source of information for anyone interested in learning more about the process. I've already had a bit of fun with this recipe.

-David Driscoll