Guyana: Day 2 – DDL Diamond Distillery

David OG made a great point during one of our various, long, detailed, and magnificent conversations about rum today. He said, "When we talk about whiskey we're talking about various types of spirits with different flavors, but most people think rum is just one thing." It isn't, however. There isn't one type of rum, just like there isn't one type of whiskey, and there's no better example of that fact than the Demerara Diamond distillery where more than twelve stills make a multitude of different rum styles with numerous flavor profiles. For the El Dorado brand, DDL has a distinct advantage with their historical distillates that couldn't be produced or recreated anywhere else.

We know that DDL has a long and storied history, but I'll get more into that tomorrow. Let's focus on just the incredible distillery for now because there's a lot to talk about. The Diamond campus, which consolidates stills from three other former distilleries (imagine if the stills from Port Ellen, Brora, and Rosebank were all moved into Caol Ila), is one of the most diverse and fascinating spirits facilities we've ever visited. Everything is happening right in front of you, out in the open, and it's all self-sustained. The boiler room, which you can see here, begins the process by powering the facility with steam. It's run mostly by methane, which is created by fermenting the spent rum wash and trapping the resulting gas. They installed it in 2010, which ended their dependency on oil.

Like we've seen at Four Roses and Wild Turkey, yeast is an important factor in keeping the flavor profile of El Dorado consistent. They have an entire room with four separate vats dedicated to the propagation of yeast cells, derived from a combination of both local strains and purchased distiller's yeast. You could smell the fruity, almost white wine-like aromas drifting out of the steel tanks.

That yeast is unleashed into a house formula of one part molasses to four parts water, creating a sugary liquid with a Brix level of 19. All of the molasses comes from Demerara sugar cane, grown specifically along the Caribbean coast. Guyana is an incredibly fertile land. It's said that if you eat a piece of fruit and accidentally drop a seed, you'll likely return to that spot later and find a small tree growing where you left it. Part of this fertility is due to the fact that the coastal regions of Guyana are actually below sea level; it was originally colonized by the Dutch, who were very good at draining the land and creating cultivatable space.

Guyana is also quite close to the equator with a temperate maritime climate, allowing for perfect growing conditions. Their sugar cane is therefore some of the finest in existence, and the by-product of this cane – the black strap molasses – is some of the best for fermentation. There are eight closed fermentation tanks at Diamond distillery, along with five gigantic open vats. They distill around the clock and almost every day of the year.

But let's get to the stills because, really, this is why we're here. What needs to be stressed before we break down each device is this: the El Dorado rums are not simply the same rums at various age levels. The 15 year is not simply an older version of the 12. The 21 year is not simply an older version of the 15, and it's not just different barrels from various parts of the warehouse that distinguish them from one another. They are all different combinations of rum from a formula that uses various combinations of the individual distillates. For example:

- the 3 year old uses mostly light to medium-bodied rum from the Savalle still with a bit of the copper column still.

- the 12 year is comprised of rums from the wooden Coffey still, the copper Coffey still, the double pot, and the Savalle still.

- the 15 year uses a majority of rums from the single and double wooden pot stills, giving it a more robust flavor.

To understand each of the selections, however, you have to understand what makes each still unique, and how that uniqueness affects the ultimate flavor. The EHP wooden column still, which you can see in the above photo, is said to be an exact replica of the first still built by Coffey himself in the 1800s. Even the plates inside of it are wooden and the spirit distilled from it is incredibly unique when compared against the standard copper version.

Then you've got the Port Mourant double wooden pot still – an antique built in the 1700s from local Greenheart wood (also used for building ships) valued for its incredible durability. The still is completely heated by a steam pipe that injects the piping hot vapor directly into the liquid. The escaping alcohol vapors are then condensed directly into a second wooden pot still that uses the incoming heat from the vapor to create a second distillation. It's not over yet, however, as the second distillation passes through a gigantic copper rectifier to increase the ester content before the final condensation.

Speaking of esters, there's an all-copper "high ester" still right next to the PM double pot. Esters are the aromatic and flavorful compounds found in fruit and flowers that we taste and smell when we interact with them. In distillation, they're the result of the fermenting alcohol coming into contact with the leftover acidity. When slowly dragged over copper while vaporizing, these compounds become highly pungent and the "high ester" still is specifically designed to maximize their intensity by increasing their exposure to the metal. For example, the Savalle still creates a spirit with about 20 ppm of esters and the double wooden still about 50 ppm. In contrast, the "high ester" still results in a spirit with 10,000 ppm of esters, which is mind-boggling because at 50 ppm you're already tasting the esters in the PM distillate. Tasting rum from the "high-ester" still is like numbing your tongue with intensity, rather than alcohol. It's absolutely insane and difficult to describe.

Then there's the single wooden pot still taken from an old Versailles distillery (Versailles is a small town West of Georgetown on the way to Uitvlugt) that adds a another antique option to the mix. Keeping up the heritage and quality of production is very important to El Dorado, or else there would be no reason to use these old things. Making rum in the wooden pots is three times more expensive than using the column stills, so there's no economic motivation. Each batch also takes 16 hours as the wood helps to maintain the vapor inside the still longer than a standard copper pot would.

The jewel of the Diamond estate, however, might be the Savalle still taken in the late 90s from the former Uitvlugt (pronounced eye-flut) distillery. Because of the various columns and how they are arranged, it's possible to make nine different rum distillates depending on how much you want to rectify the spirit. There's the possibility of total neutrality, or a floral and fruity distillate that makes you want to sing! The forth column is specifically designed to enhance the natural flavors in the fermenting wash, so there are a lot of options.

Then there's the standard copper Coffey still, which does the same as the wooden still, but rather with more copper contact for a higher ester content. El Dorado's master distiller is Shaun Caleb, a Princeton-educated Guyanese local who spent years working under the legendary George Robinson. When George passed in 2012, the torch was given to Shaun who was expected to lead DDL into the future. I think they made the right move. Shaun is knowledgeable, kind, and humble. He listens more than he talks, which is always a good sign. The man knows as much about distillation as anyone I've ever met.

Of course, there's the "new" still, which you can see all the way from our guest house – a gigantic monolith that can crank out 15,000 gallons of spirit a day. That's where the majority of the bulk spirit comes from. We did get a chance to taste white spirits from each of the stills and the differences are highly noticeable. Being able to blend from various distillates is a huge advantage and it's something that Diageo pays heavily for with their Johnnie Walker whiskies, blended from a number of different distillates from various distilleries. Here at DDL, it's all done under one roof.

Between their five warehouses (they still use the old sites of Uitvlugt and other estates for their storage, a la Kentucky producers with Stitzel Weller and Old Crow, etc.), DDL has more than 100,000 barrels aging around the country. 20-30% of that stock is sitting at the Diamond estate. The barrels are stacked vertically to maximize space and the hot, humid climate causes the spirit to evaporate much faster than our cooler conditions at home. It's not uncommon to lose 50-55% of the barrel over time. Much to my surprise, there is absolutely no sherry maturation happening at DDL. All of their rum is aged in refill Bourbon casks that have been stripped and re-coopered to expose more of the fresh oak underneath the char. The sweetness is simply due to rapid maturation and evaporation under the extremely humid conditions. No barrel is used more than five times (for younger rums) or ten years for the older stuff. After a rum passes ten years in wood, it's racked into a new barrel.

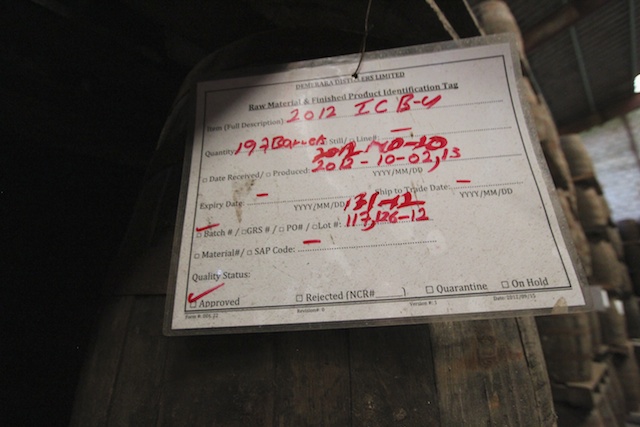

With so many distillates going into wood, how do you keep track of what's what?! Very carefully.

We took a break after our tour and later in the evening went into Georgetown to have dinner with DDL Chairman Komal Samaroo. We're really looking forward to working with him and his team. I cannot express to you how fantastic it is to have the opportunity to express your aims and goals with the person in charge of operations. It's entirely different than meeting with a sales rep or assistant and I think we really communicated our hopes effectively. It was an exciting moment for both David and myself.

-David Driscoll