Oaxaca 2015: Day 3 – Los Danzantes

About thirty minutes outside of Oaxaca City sits one of the most-heralded production centers of mezcal in the region. I don't know that I'd call it a modern distillery, but Los Danzantes has what is by far the most efficient and streamlined operation I've yet to visit in Oaxaca. It's still pretty much a hands-on facilty, but everything looks orderly and well-maintained. It's both rustic and highly-functional. Three pot stills on the main floor next to the fermentation vats (to make the transfer of fermented agave much easier) and two additional pot stills on the upper level for wild agave distillation and projects that require more attention. I was really, really impressed with their outfit.

The roasting pit sits at the back of the open air space, right next to the loading dock where trucks periodically pull up to make an agave delivery. They drop the agave right next to the pit, making it a cinch to roll them over into the coals. From there it all moves downhill, which allows gravity to help with each transition. The stone tahona pit is just beneath this, so all you have to do is roll each piña over to the next station.

Once the piñas are mashed, they're fermented for five days or so in wooden vats before the materials are cooked and distilled in the gas-powered pot stills. They look like gigantic barrels full of carnitas.

Unlike with most tequila, Danzantes is actually putting the pulp and the fiber into the still during distillation. Tequila production strains out all the agave fiber and boils only the sugary liquid when distilling. That makes a huge difference in the intensity of the agave flavor. Keeping extra contact with the solids during the entire process can be a stylistic choice of various producers. For example, some vintners like to punch down the cap when fermenting wine (pushing the skins back down into the liquid so that they impart more flavor into the final product).

Despite the logical layout and the clean quarters, everything at Danzantes is still done by hand on-site—from the beginning to the end of the process. Even the bottling is done in a small room to the left of the entrance, where a group a workers sit and release the mezcal out of a water cooler-like device. There's very little technology at work here. The entire distillery operates in a space about the size of the Redwood City sales floor.

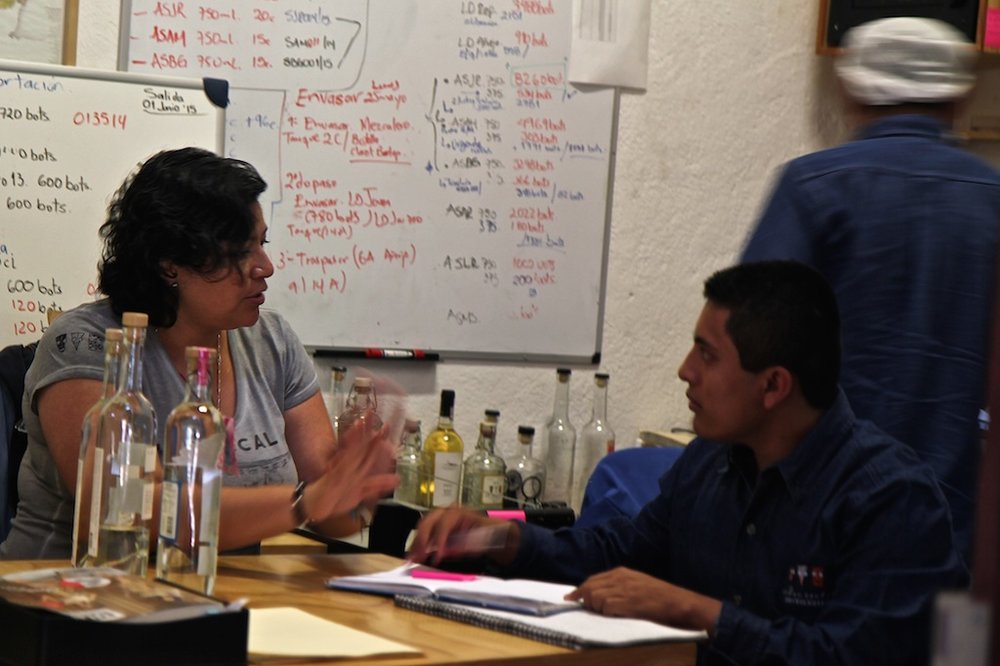

Next to the front door sits the office of Karina Abad Rojas—the head of production for Danzantes and one of two main distillers at the facility. I said I was going to tell you more about her later, and now seems like as good of a time as any. This woman is nothing short of amazing. She is without a doubt the most competant distiller I've ever met; in the sense that she not only knows everything about the science and the chemistry of distillation, but also about the agricultural background of the base product itself. Unlike most of the Danzantes management (from Mexico City), Karina is a native Oaxacan who knows the terrain like the back of her hand. She can tell you what the soil looks like in the mountains along the Pacific Coast, how that specific tierra affects the sugar in the agave grown there, and what those conditions will ultimately translate to flavor-wise when distilled. Not only can she tell you all of these things, she can do it calmly and with complete patience. She's not only a great distiller, she's the best educator I've yet to meet in this industry—and I'm communicating with her in a language in which I am far from fluent. She takes the time to speak slowly, in detail, and with a sly smile so that you know she's enjoying herself as she does it. She summarizes concepts clearly and with easy-to-understand analogies. She's humble when she describes her work, with no ego, and no chip on her shoulder whatsoever. She's more interested in listening than talking, but won't hesitate to chime in when something needs to be said. I've been glued to her side for the last 48 hours because I can't get enough of her. This woman is the epitome of talent and grace when it comes to the booze business. If I were going to put the future of mezcal into anyone's hands—as a spokesperson or beacon to lead the industry forward—Karina would be my first choice, by a long shot.

We've long sold the Danzantes mezcales at K&L (now known as "Los Nahuales" in the U.S. due to a trademark issue with the Danzantes name), but until today I never really understood where they stood in comparison to the other selections we carry. They're following the tequila model, which is the standard blanco, reposado, and añejo progression; choosing to market familiarity rather than specifics. The brand has actually enjoyed more success abroad with the Alipus portfolio, simply because of the wilder flavor profiles and the romanticism surrounding the remote locations of production. The reason Danzantes was struggling a bit in comparison was clear to me after today. Simply put: the Danzantes mezcales are too well-made! Seriously. They're so clean, so well-crafted, and so pure in flavor that they get completely obliterated by some of the more intense and powerful mezcales coming out of the mountains. If you need a whisky comparison, think about Clynelish in comparison to Laphroaig. Far more whisky drinkers appreciate the latter distillery, but most experts I know admire the former for its delicacy and grace. Karina's mezcales are the Clynelish of the agave spirits world. She's too talented of a distiller for her own good because far more consumers appreciate intensity over balance.

I could sit and talk to Karina all day (and I actually tried to today, following her around like a puppy dog while she worked). We chatted in her office about a number of different subjects—from the best locations for wild agave harvesting to analogies in the wine world—while I tried to get a better sense of her role at the distillery. That's when I spotted a number of bottles along the back of her desk.

"Que está en esta botella?" I asked, looking at the hand-written label out of curiosity.

"That's a special project I've been working on," she said. "It's for the Arte de Mezcal series," referring to a label not available in the states. Danzantes has been working on a project called Arte de Mezcal that utilizes some of the more creative and experimental batches of mezcal distilled on site, while allowing Karina to pursue her own interests and push herself further as a distiller. "I've always been a big fan of sierrudo," she continued. "It's a cultivated species that gives off flavors of cherries and dried chile." When Karina first started experimenting with sierrudo, she thought the species had potential for greatness, but it needed to be combined (co-fermented, not blended) with another type of agave to help balance out some of the fruitiness. That's when she got the idea of including in a bit of cuishe into the recipe—a wild agave species known for dark chocolate flavors and notes of bitter herbs.

"I think the combination of these two creates the harmony between the flavors I've been looking for," she said further, grabbing the bottle to pour me a taste. I took a sip and let the mezcal linger on my tongue. It started with citrus and sweet agave spices, then moved into a clean, yet vibrant display of pepper, roasted fruits, and cinnamon. The finish was fresh and lively, with the clear flavor of sweet roasted agave present on my palate for minutes after I swallowed. It was incredible.

"What are you going to do with this?" I asked coyly.

"I'm not sure yet," she said.

"I have an idea," I answered with a huge grin.

At that moment, however, another truck filled with agave parked itself at the back entrance, so we had to table that conversation. It was time to get our hands dirty. We could talk business later in the evening.

-David Driscoll