Kentucky 2015 – Day 4: New Lessons, New Perspectives

In all our years traveling together on the road, David and I realized recently that we'd never actually visited a full-scale cooperage. We've seen a barrel or two being formed, and I'd seen the charring on site at Kavalan last year, but those operations are small potatoes next to something like Brown-Forman's Louisville center. The family-owned company is the only major whiskey producer to use barrels made entirely by their own cooperage production, and when you think about how many bottles of Jack Daniels they're selling per year, the number of casks they produce annually is in the millions. The Louisville site alone does more than 500,000.

No matter how many times you've been to a distillery, no matter how many tours you've particpated in, you always learn something new when you visit a producer (which is why I always let them go through the whole general routine rather than try to dictate the program like some pompous ass who thinks he knows everything). I guess I always thought "seasoned" staves meant the planks were toasted or dusted with cinnamon and spice (not really), but seasoning a stave means you just leave it outside for a while. Literally. You just put the wood outside and let the natural elements breakdown some of the structure of the stave. This massive load of palletized and seasoned staves will last the Brown-Forman center only until the end of today's shift. There's a whole lotta cooperin' going on in these here parts.

If you've never watched a Bourbon barrel being formed (either on video or in person), I'd highly recommend taking the tour through a cooperage site, just to have an appreciation for the art. There are no nails and there's no glue. It's all form, pressure, and proper hoop work.

And don't forget the charring! Bourbon must be aged in new charred oak by law, so there's a whole lotta charrin' going on in these parts to boot.

Since David and I were trying for a new set of experiences today, hoping to visit some fresh faces and learn more about the industry, we drove out to Woodford Reserve to take a tour of the distillery. We were early, however, and since Versailles isn't all that far from Lawrenceburg, we thought we'd drop by the Kickin' Chicken to see what was happening. I love their new tag line because it pretty much sums up the way we feel about Wild Turkey whiskey at K&L. It never gets old, and it's always good. I still think Wild Turkey is an incredibly underappreciated Bourbon among the geekier crowd.

And look who was there to greet us! Our old pal Jimmy Russell, the legendary 81 year old master distiller who's still fresh as a spring chicken (or turkey, I guess). He wanted us to taste his new 17 year old Master's Keep, a pricey but undoubtedly delicious new Bourbon just released by the distillery. We loved it, but I thought maybe a few serious afficionados might find it too soft at 43%. Being the oldest whiskey ever released by Wild Turkey, it's definitely on the smooth side, but utterly mellow and easy-going with a long, creamy finish. "There's a reason for all that," Jimmy told us as we tasted. Then he told us the story behind the casks. All of a sudden we got much more excited. I even called my rep from Wild Turkey and had her order a bunch of extra cases (you might even see these pop up today if you check the website later—the box and bottle are stunning, some of the best packaging yet in the Bourbon industry).

I don't want to ruin the story before we actually start selling the product, but it involves this little place along McCracken Pike—the former Old Taylor distillery—long abandoned, but recently purchased by a new investment group who is currently remodeling the site. We stopped by to check up on the progress.

And it involves this building nearby. I was trying to figure out why the label said: "1. Wood, 2. Stone, 3. Wood". Now I know. Turns out 43.4% is pretty much cask strength in the case of this particular whiskey. More on that later.

I probably know less about Woodford Reserve as a whiskey than any other product we carry. I never drink it. We don't sell a whole lot of it. The last time I tasted it before today was probably five years ago. It's just that flat little flask-shaped bottle that people buy in the store from time-to-time—nothing more. That being said, I can't stress to everyone out there enough how important it is to visit some of these big-brand distilleries. Many of the assumptions you have about their production methods and philosophies might be more inline with your own than you think. I thought our tour today of the Woodford campus was fantastic and it really endeared me to the whiskey in a way that had been completely absent previously. Much like Maker's Mark, I think you'll find that Woodford looks and feels like what you expect from the Kentucky Bourbon experience. Minus the giant pot stills, of course. Woodford makes whiskey more like Redbreast or Glenmorangie, than it does your standard Bourbon plant.

Sure, Woodford Reserve is made on Scottish-style pot stills, but it's also blended with column still Bourbon from Brown-Forman's Shively-based distillery before bottling. The corn/rye/barley mash is cooked and fermented just like at any other distillery, but what's interesting is that the liquid is then distilled with all the solids still inside. It's triple-distiled much like an Irish whiskey, then put into new charred oak like Bourbon.

What's perhaps even more interesting than Woodford Reserve's whiskey process is the history of the location itself. Brown-Forman can trace distillation at the Woodford site back to tax records from 1812 when Elijah Pepper founded his distillery there. His son Oscar Pepper eventually took over the reigns and was one of the first people to employ a master distiller, in this case a man named Dr. James Crow (you might recognize him from the latter half of the name Old Crow). Dr. Crow was one of the great pioneers of the Bourbon industry, utilizing science and laboratory efforts to create better whiskey. His papers on charring the inside of the oak cask and using the spent mash to help start new fermentation (or the sour mash process) were revolutionary in their day and helped shape the nature of what Bourbon is today. To think this all happened right here, in those very buildings, is pretty cool. Another interesting aside is that Brown-Forman actually owned the distillery previously during WWII, but sold it off when the industry died in the late fifties. They bought it back in the early nineties and released the first bottle of Woodford Reserve in 1996—so it's a fairly new brand in Bourbon context.

I also quite enjoyed the overall perspective of the whiskey process we were presented with at Woodford, all the way from barrel dumping and charcoal filtration, to batch creation and blending. They were incredibly hospitable and transparent from front to back. I was really impressed by their professionalism on all levels.

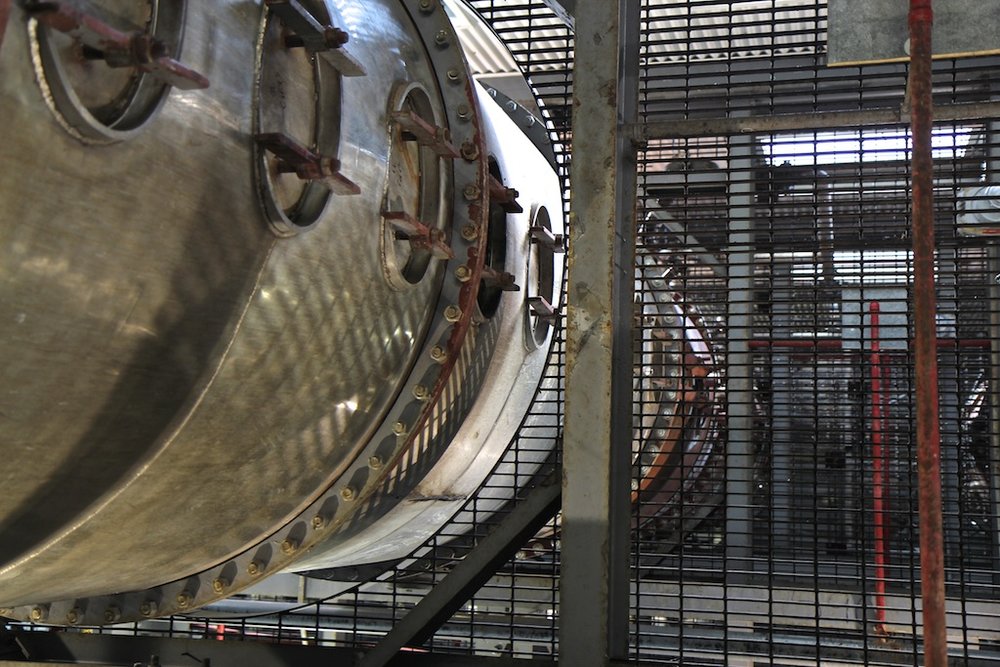

Back in Louisville later this afternoon, we finally convinced Heaven Hill to let us into thier Bernheim plant, which is the opposite of Woodford Reserve in every way imaginable. Bernheim is a gigantic factory forged of metal and steel with chain link fences and grated floors. They have almost twenty 124,000 gallon fermenters that dwarf anything we've ever seen, and mash tons that have huge propellers turning with flabbergasting force. It's one humongous operation!

The two massive missiles they have for column stills span multiple floors and rise out of the bowels like industrial motifs of power and force. I felt like I should have been counting down for lift off!

After a great visit with Phil at Bernheim (the guy has moonshining stories galore!) we drove the couple miles down to Shively to see if we could sneak a peak at the Early Time distillery. Brown-Forman does not allow anyone into the location, but I thought I might be able to convince the security guard I had priority access. No dice. It's not a place they want anyone to visit, nor to find either. The gated entrance is at the end of a long driveway off the main road that you'd never notice if you weren't looking exactly for it.

In all honesty, I'd seen enough for the day so I wasn't too disappointed. I needed a cold beer at that point.

-David Driscoll