D2D Interview: Lorenzo di Bonaventura

Movies were everything to me when I was a kid. From the time we got our first VCR, I spent every free minute watching every movie I could get my hands on. In high school, I worked in a video rental store to increase my exposure (and to get free rentals). I even graduated with a film degree in college because I thought I was going to make movies one day. There were two problems with that plan, however:

1) Like many young people today, I thought the fact that I was excited about something also meant that I was good at it. Realizing that passion and talent don't always go hand-in-hand is a hard truth to learn when you're young.

2) I also discovered that I didn't like making movies nearly as much as I liked watching them.

After working my first real gig (doing sound for an AMC documentary about John Malkovich), I decided to give up the dream and go into teaching. Today I sell booze and write this little blog for a living, but never did my love for cinema ever diminish. For that reason, getting the chance to talk with the people who actually made it in the movie business absolutely fascinates me. It turns out that a lot of Hollywood people like drinking wine and whiskey (and shopping at K&L), so our paths seem to cross every now and again. Take Lorenzo di Bonaventura, for example. The man loves drinking wine and he also has quite a taste for spirits. Having worked at Warner Bros for years, Lorenzo has helped produce many a famous movie, but today he runs his own production company (di Bonaventura Pictures) out of Paramount. You may not recognize his name, but he's the guy behind just about everything you've grown to love over the last few decades. Ever heard of a little, low-budget, off-the-radar, science fiction series called The Matrix? He made that happen. He also purchased the rights to a teeny-tiny little book series called Harry Potter and helped bring those stories to the silver screen. Nothing major, right? But nothing to shake a stick at either (HA!).

More recently at Paramount, Lorenzo's known for developing and producing the Transformers franchise, and a number of other flicks you've probably seen more than once. I know him mainly, however, as a guy who has great taste in wine and even better taste in rum. In this D2D interview, we compare and contrast the film industry to the booze business, discuss being recognized in the strangest of places, and the fact that—just like with alcohol—there are times when you take film seriously and times when you just need to have fun with it.

Previous editions of the D2D interview series can be found by clicking here, or the link in the right hand side of the margin.

David: From what I understand about motion picture production—which isn’t insignificant, but isn’t all that much either—you pretty much have the same job that I do, right? Except that instead of buying and selling cases of alcohol and explaining their merit, you buy and sell million dollar movies.

Lorenzo: There is some similarity. I would say this: you try to find value and quality, and that’s what I try to find as well. The job is to see value where others don’t—sometimes with a vintage or maybe with a different chateau that other people aren’t paying attention to. The first movie I ever got made was a script called Falling Down.

David: No way! I love that movie! It also reminds me of some whisky geeks I know (laughs).

Lorenzo: Yeah, it became a really good movie; I’m very proud of it. It was sent to me as a writing sample, and most people didn’t think it would get made because they thought it was too dark, too weird. But I read it and thought, “I love this idea for a movie.” The producer was actually kind of incredulous at the time—I was a studio executive then—and he said, “You guys are never going to make this film.” But eleven or twelve months later we were in production, so you try to find the hidden gems. My job is essentially to nurture these things. If there’s a wine analogy in there, it’s with the vines: you give them water, love, and you hope the weather’s right. Ultimately, that material will drive the equation of whether the movie gets made or not. Will it attract a big director or a big writer, and will a studio want to finance it? I spend a lot of my day planting seeds.

David: Would you say that a certain amount of passion or belief in these products can drive them and make them successful?

Lorenzo: I think so. It’s such a business of “no” and rejection, that if you don’t have the passion you’re not going to succeed. I think passion comes from perseverance—or desperation, but of course those two things merge in our businesses. You get “no” over and over again. When I submitted Transformers originally to my home studio I was passed over five times. It was either the fifth or the sixth time that I brought it back and said, “There’s something here, guys,” that they finally bought it. So it does really require a belief or the courage to go against the grain of where people think taste is leading us. I’ve never been a fan of big California wines because they overwhelm my taste. But you can’t make a blanket statement like that and really like wine, right?

David: Absolutely not. You can’t write anything off if you’re a professional.

Lorenzo: The truth is, however, I like layering and subtlety.

David: But that also doesn’t mean that you deny the quality of the wine, or its ability to appeal to others. It just means you personally don’t like it.

Lorenzo: Exactly. I recognize a big California red and every once and a while I’ll drink one.

David: This leads me into something I wanted to ask you concerning Transformers. I read an interview where you talked about the fact that, despite negative reviews from the film press and people who think they understand “quality” cinema, the franchise has gone on to be one of the most successful in movie history. Millions and millions of people loved those movies, so how can you say they aren’t any good?

Lorenzo: There are snobs in every business, right? There seems to be a current of thought that goes out in our world—in fact, it’s reflected in the Oscar nominations—that big is somehow not good. Or to put it differently: small is good.

David: Tell me about it. I’ve been one of those people before (laughs).

Lorenzo: I don’t accept that, though, and I live it. I’ve had some of the craziest experiences with fans from of the Transformers movies and I’ve seen their passion firsthand. I say God bless these fans because without them we’re nowhere! I was in Malaysia for Christmas and—God knows how—one of the gardeners at the house figured out I was the producer for Transformers. He had to come up to me and he had to tell me that he’d seen the movie not once, not three times, but five times. He brought his wife to see it one time, his kids another time, and his friend the time after that. I ended up giving him the Transformers hat I was wearing because it was clear how much he loved the film. Another crazy story involves me on an operating table in London getting an angiogram, when the technician said to me, “I just have to ask you: are you the producer of Transformers?” At that point, I’m thinking about my life! Life and death, you know? I said I was, and he said, “I’m the biggest fan. Every day after school I would go home and play with my Transformers. I’ve got 500 of them.” He went on for another few minutes and then he stopped and looked at me and said, “Maybe this isn’t the right time for this conversation.” I looked and him and said, “You know what? Keep talking, man. This is the first time I haven’t thought about life and death in the last few hours!”

David: That’s hilarious! (laughs)

Lorenzo: So he kept going. “I’ve got Optimus Prime boxers, Bumblebee boxers, Megatron boxers.” Then he said, “Oh my God! I think I’m wearing some now!” So he took his pants down and sure enough he was wearing Transformers boxers. Now some people would say this Transformers stuff is too commercial or lowest-common-denominator, but I don’t see it that way. I see real passion and real care from these people. They love it! And we’re providing something to them that means a great to them in their lives. That’s what I think critics often miss about some of the bigger movies. The audience is looking at them in a different way. People are savvy, they know when we’re not trying for the deepest character development. We’re ultimately trying to give them an experience and they validate that experience. That’s where there’s a disconnect between certain critics, or pundits: they sometimes don’t get that there are two different kinds of films and they both have validity.

David: You really just put your finger on my main motivation for doing these interviews. I felt the blog I was writing was unintentionally reinforcing a specific kind of serious spirits connoisseurship without balancing that mindset with a more-relaxed and easy-going approach. I was stressing too much analysis and not enough enjoyment. It was all about details and not enough about fun, so I wanted to talk with other people in different industries to see if I could gain some perspective about this issue. In having these conversations, no one has reiterated as clear of an exact analogy as you just did. It’s the same message that I want to send to all of my spirits clients; that there’s more than one type of drinking experience out there and that they all have their time and place.

Lorenzo: So I grew up in an Italian household and the celebratory drink was always Asti Spumante. I have warm childhood memories of it, it’s never been a particularly expensive wine, and as I grew older I discarded it. I probably haven’t bought a bottle of it in thirty years. I’m part of a wine group here that meets for dinner—it’s really just an excuse for overconsumption—and we usually go from eight dollar bottles to as expensive as it can get. We like trying crazy wines from all over the world. One of the guys at one of the dinners put a bottle of Asti Spumante on the table one night, and I said, “Really? Come on.” We drank this Spumante, however, and it was staggeringly good. It was fresh and vibrant and not particularly sweet. It was such a great bottle—I think it was around eighteen dollars—and I bought a case.

David: That’s kind of the Ratatouille moment, right? I don’t know if you saw that movie. Where the critic sees the plate of actual ratatouille and doesn’t think it can be great because it’s normally a peasant dish, but ends up flashing back to happy memories of childhood.

Lorenzo: Exactly right. I think in this case, however, my childhood memories weren’t exactly negative, but I wasn’t ever in a hurry to have Asti Spumante again.

David: Another quote I read from you in a different interview was about film critics who compare films that shouldn’t necessarily be compared to one another. I have that same issue when dealing with alcohol. Sometimes a customer will come in and ask, “I see you have this great deal on $10 Bordeaux. How would this wine compare to Chateau Latour?” Or something like that. Everyone wants to know how some cheap, inexpensive Bourbon compares to Pappy 20, but they’re not things that should be put next to one another. Your quote had to do with someone comparing Transformers to a Martin Scorsese drama.

Lorenzo: Right, they both have their own individual values, but they’re obviously not the same thing. I’ll tell you about a wine that I love, a California red actually: the Shafer Hillside Select. What’s interesting to me is that it’s the closest wine I’ve tried in flavor to the Haut-Brion red. I’ve always loved the sort of granite taste that I get from Haut-Brion and the first time I found a wine that had anything similar it was while drinking the Shafer. I loved it. Now one of them costs—well, actually both of them cost a lot now—but when I first tried them there was a huge disparity between the two prices. Even then, however, it’s not fair to compare them. They’re both great, but you’re buying each of these wines for different reasons, so why don’t people judge them for different reasons? America loves to compare things. They like to ask: which is the best?

David: Oh Jesus, don’t get me started on that. That’s my hot button trigger, right there. So what do you say to that, when someone asks you what’s “the best”? Hey Lorenzo, what’s the best movie you’ve ever made?

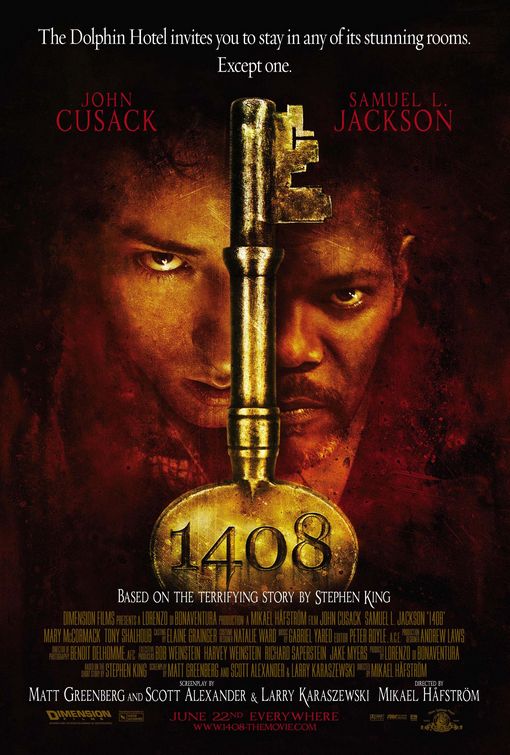

Lorenzo: I wouldn’t ever call one of my films my “best” movie, it might just be my favorite movie. I like different movies for different challenges. We made a movie called 1408 and the challenge in making that film was: can we make a 90 minute movie while staying in one room? That was a cool challenge and I really like what came out of it, but that’s a very different challenge than say Constantine with Keanu Reeves where we had to examine the meaning of heaven and hell, or good and bad. They’re completely different things. So my answer to everyone is: I can’t pick a “best” film. Each of them I appreciate for a different reason.

David: Do you think this mindset of “the best” has become worse, or do you think it’s always been the case in America? Is the idea of summarizing everything quickly into a top five or top ten list becoming more of a crutch?

Lorenzo: I think it’s become really compulsive. Actually, as it concerns the movie business, I remember the moment it happened. I was traveling and I remember thinking at the time, “My God, did something just profoundly change?” I do a lot of adventure sports and white water rafting, so I was at a crummy little motel in the middle of nowhere, Idaho. I was on my way to a river trip and I was watching the news on TV. On the news they said, “The number one movie this weekend was: so-and so.” For the longest time, no one ever did that. No one ever reported what the top-grossing movie was for the week. We forget that now because it’s become such a part of our world. “The number one movie in America!” I thought to myself, “The whole business has just changed,” because when you talk about number one you automatically push out other movies. The importance of being number one has a real financial implication because the audience responds to that kind of advertising. “Oh, that’s the number one movie? Well, maybe I should see that.” I’m not suggesting in any way or form that these people are not sophisticated, but that’s what advertising is meant to do: it’s meant to attract people, and people like to know what’s happening. If you’re told by the news that the happening movie is this particular one, then what happens to all the other movies playing? They get pushed out. Less attention can be paid to them, and that has had a profound effect on how movies are sold and selected.

David: I can see the booze parallels already.

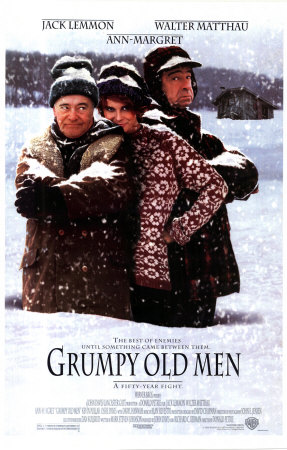

Lorenzo: It used to be that a movie could run for weeks and weeks without issue. Years ago I did a film as an executive called Grumpy Old Men. It never did more than four and a half million dollars at the box office, but it did so every week for like fifteen weeks. Now there’s no room for a movie that can only make that kind of number. There’s not enough shelf space. That movie today would never turn out to be a hit.

David: That’s very interesting to me because, were I to ever write a dissertation about the booze industry, it would be about how companies are catering to the general ADHD of the moment. Retailers, advertisers, booze companies need a new product every week to keep the public’s attention, until they can discard that product and replace it with something new. So you keep seeing the same brands trying to reinvent themselves with new versions of the same thing, hoping to get back on the radar for that point in time. The customers absolutely respond to that, but what happens is: rather than come back and buy a second bottle, they look for the next hot thing. Everything is focused on what’s next. So how can you build longevity or understand what makes something great when you can only pay attention to it for two seconds? That’s why each company needs to have fifty different products, whereas a decade ago maybe they only had five. They know they’ll only have a few weeks in the spotlight before they’re pushed out for the next new thing.

Lorenzo: What’s ironic is that it’s a bit of a self-fulfilling prophesy. If you’re going to spend your marketing money that way, then people are going to come, which only reinforces why you spend it that way.

David: Absolutely. It’s entirely of our own making.

Lorenzo: That’s absolutely true in the movie business, too; without question. There are always exceptions, but as a rule this process tends to push out certain smaller films. At that moment in time when we made Grumpy Old Men no one thought you should make a movie for fifty and sixty year olds, but actually it was a really good idea; a very profitable one for Warner Bros. It even got to a sequel. For me, I like diversity in life—period. I want more movies. I want quality movies.

David: So what do you say to someone who says: “I don’t have time to watch all these different movies. I just need to know what the five best movies are so I don’t waste any time on the bad ones.”

Lorenzo: It’s part of what we fight for: the public’s limited amount of leisure time. I guess, like with DVDs, you can bring the wine home rather than drink it out at a restaurant, right? Netflix has intruded on our business, I’m sure ultimately in a positive way, but there’s been a big readjustment going on around it. I’m happy to tell people what my favorite movies are, but I also push them to try and find their own thing because that’s what’s fun about our business: everyone gets to have their own opinion. Who’s to say your taste of wine is any more legitimate than so-and-so’s? Somehow there’s this notion that someone who by definition is an expert somehow is more right than you. I don’t think that’s true. You have your own taste, so whatever your own taste is dictates the right choice for you.

David: But there’s a fear of making the wrong decision. I guess it’s not as prevalent in the film world because ultimately the most you’ll ever waste on a bad movie is fifteen bucks. But you might pay $100 or more for a bottle of alcohol that winds up not hitting the mark. People want security against a bad investment.

Lorenzo: I can see that.

David: I’m sure there’s still a film industry analogy though. For example, what do movie companies do to secure themselves against bad investments?

Lorenzo: Well, they do everything they can. They sometimes will sell off pieces for different prices, they’ll bring in equity players, and they do other things to take away risk from themselves; as much as they possibly can, actually. Sometimes it works and sometimes it doesn’t. The problem I’ve found—if you want to look at it purely from a business view—in trying to reduce your risk from this piece or that is: how do you know that the idea you’re cutting isn’t the grand slam idea? At Warner Bros there was a famous story right when I got there about how Home Alone was put into turn-around over a two-million dollar argument. Now that movie eventually went out and made billions of dollars, so was the guy who put the brakes on wrong? Well, it appears that way now, but to his eye at that moment in time it wasn’t the case. So it’s an interesting reality we all face because we have a product that’s uncertain. We make a product that sometimes won’t go out for two or more years.

David: That’s a lot like wine or whiskey, too.

Lorenzo: Yeah, I guess it is, isn’t it? But we sometimes are making wines—to use the analogy—that have never been made. We’re making a movie where the notion of it has never been out there. We have no idea if the audience will accept it. Sometimes you see these legendary bombs—I’ve been involved in a few—where you thought you were going down the right path, and thinking about all the issues, but you find that the audience doesn’t like the taste of that one. There’s no recourse at that point though; there’s no recovery. So it’s a sort of instantaneous death.

David: This is all so similar to the booze business. As someone who thought he was going to grow up and make movies, I have to say that I’m really enjoying this conversation. There are so many more things I want to ask you about making films, just for my own personal interests, but I have to keep this at least somewhat booze related! What are you drinking on a regular basis when you’re not busy making motion pictures?

Lorenzo: I’m an equal opportunity drinker. If you saw the bar in my house you’d be very happy (laughs). Overall, I probably drink more red wine than any other kinds of wine, and I probably drink more vodka than any other types of liquor. I’ve always been a Bourbon drinker since college, so I would say that I tend to go through cycles where I’ll drink a lot of Bourbon, or vodka, or rum—I’m a big rum drinker, too. If Tequila didn’t hurt so much I’d drink more of it. I tend to like old world wines over new world wines because I seem to have a physical reaction to a lot of the California wines. There’s something about them, but I can’t exactly say what.

David: It’s probably the higher alcohol and sugar content. That extra 3-4% really sneaks up on you. I’m the same way, hence why I drink mostly old world wines as well.

Lorenzo: Maybe that’s it. But when I drink I tend to drink the whole bottle myself, so that probably negates that theory over the long term (laughs). More subtle might be the wrong word, but I usually like the older California brands, or I respond better to them.

David: Same for me. Usually they’re more restrained and the alcohol is lower.

Lorenzo: Growing up in an Italian household, I grew up drinking largely European wines. California was somewhat alien to me, so I’m probably not as versed on the subject. I tend to drink more French, Italian, and Spanish because that’s just how I grew up, so I usually drink only a few select California wines. I like the ones I drink, but again that physical reaction makes it a little hard to get completely excited about doing it.

David: Well, your tastes pretty much mirror mine. I didn’t grow up drinking European wines, but I’ve come to enjoy them more than California wines simply because of the restraint. Much like you, I enjoy drinking the entire bottle once I open it. I can drink a whole bottle of Spanish red wine because it’s usually only 12% alcohol, or a whole bottle of Italian white wine because maybe it’s only 10-11%. I can enjoy them with a number of different foods, or with my wife, etc. But if I drink a whole bottle of California zinfandel, with 16% alcohol and all that residual sugar, then not only am I going to be out for the count, I’m going to be hurting the next day as well.

Lorenzo: I never made that parallel before, but I’m going to pay attention to that now. I’d never really thought about the alcohol content playing such a role. You’re probably right about that having a real effect on me. Going back to the notion of what’s good and what’s not, I really love Mount Gay rum. People say to me all the time, “That’s a cheap rum, why not drink something better?”, but I love it. I love Mount Gay with tonic and lime. Bring it on! I’m happy.

David: I love Mount Gay with tonic. That was a big thing for me when I went to Barbados a few years back.

Lorenzo: I like Ron Zacapa, too, and there are plenty of other great rums I drink that are more expensive, but that one will always stay in my repertoire.

David: Who else do you know in Hollywood that likes drinking as much as you? Who has really good taste?

Lorenzo: Clooney comes to mind. He’s always been a hard vodka drinker.

David: He’s got a tequila now, too, so maybe he’s drinking more Casamigos these days.

Lorenzo: That’s right! Maybe I shouldn’t talk about him liking vodka so much (laughs). Hollywood is always characterized as sort of unsophisticated—loud, pushy, and that sort of thing. I grew up on the East Coast and that certainly was the impression we were given of Hollywood. But my experience has been quite different. There are a lot of people from all over with great taste and very sophisticated palates. Most of the people I know here enjoy drinking and they all like good stuff, so it’s tough to single any particular person out.

David: God, everything you’re saying is right from the script of what I wish more people would talk about when they talk about alcohol appreciation. We’re in total sync. People are going to think I put you up to this, that I’m pushing you in this direction.

Lorenzo: What’s funny is that Eric Asimov is an old friend of mine. I knew him in college and we see each other once in a blue moon, so of course I read and follow his column. I find it very interesting that as I’ve gone deeper and deeper into his world of wine, I’ve become more interested in less expensive wines and particular tastes, rather than sophistication—which is often the benchmark people try to put on things, you know? How sophisticated are you? So it’s been interesting to read his stuff and watch him head in that direction, too.

-David Driscoll